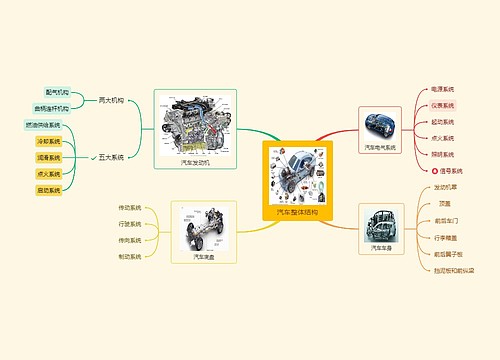

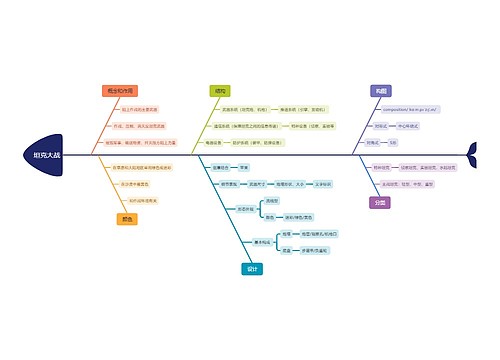

Chapter 5思维导图

U148550879

2023-10-23

批评

已解决

亚历山大

《建筑师》第五章介绍

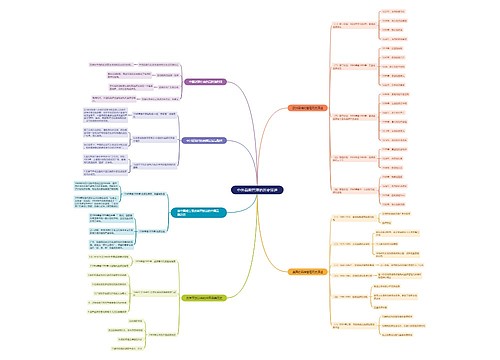

树图思维导图提供《Chapter 5》在线思维导图免费制作,点击“编辑”按钮,可对《Chapter 5》进行在线思维导图编辑,本思维导图属于思维导图模板主题,文件编号是:309c3a67e15b84a395aa6c34cb8f7b8a

思维导图大纲

相关思维导图模版

Chapter 5思维导图模板大纲

The Architect

On September 30, 1812, the

The district surveyor, William Kinnard, had indeed advised Soane that the projection violated Statute 14 George III, cap. 78, commonly known as the Building Act, which prohibited enclosed projections to extend beyond “the general line of the fronts of the houses” on a street.3 In their accounts of the case, heard before the magistrates at the Public Office in Bow Street, the

of Soane’s freehold, the line of his property, which lay several feet beyond the projection. “A common nuisance must be that which deprives the public of some advantage, or puts them to some inconvenience,” he argued, but this could not be the case at 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, where the public was not permitted to enter Soane’s freehold and thus was never in proximity to the facade.4

Figure 40.

o

Morning Post

undefinedd

Figure 41.

h

<a id="bookmark2"></a>This case was evidently of considerable interest, probably as much for its relevance to property owners throughout London as for Soane’s celebrity;

the

The irrevocable projection of the architect’s palpable eyesore into the public realm would occur two decades later when the House of Commons approved the private act of Parliament bequeathing Sir John Soane’s house to the public as a museum. It was Joseph Hume, MP (a few years prior to his crucial intervention in the rebuilding of the Houses of Parliament) who presented the case for accepting this “noble and disinterested” gift to the nation.7 Prior to the final reading and vote, the members of the House of Commons debated for the better part of an hour the legality and morality of Soane’s donation, raising implicit and explicit questions about Soane’s private character and his public reputation. Despite Hume’s endorsement, some members of Parliament found fault with the donation, questioning the propriety of alienating his descendants from the property they might have inherited; other members then stood to rebut various aspersions upon Soane’s motives. The house and its idiosyncratic architecture, the debate suggested, were a proxy for Soane’s private character. Ultimately, with Soane’s reputation successfully defended, the Soane’s Museum Bill entered into law as private Act, 3 William IV, cap. iv. With the strict stipulation that

the house and its contents be preserved in their arrangement and condition upon Soane’s death, the palpable eyesore of Lincoln’s Inn Fields became the real property of the public.

Libel

The London in which Soane resided offered countless venues for production and exchange of opinions; there were streams of correspondence to circulate news and gossip, which then made their way into personal diaries, pamphlets, or journals; there were debates and lectures, staged in drawing rooms and coffee houses, academies and Parliament. During the years of Soane’s architectural career, talk in all these forms was the medium of “publicity,” a word coined at the end of the eighteenth century to describe the condition of entering into the public sphere and being rendered an object of public attention.8 At that time, dozens of different daily, weekly, and monthly newspapers and journals constituted the London press, the most popular of which had circulations in the thousands. Although limited to an educated and reasonably affluent readership, they wielded a powerful influence with an amalgam of political commentary, literary reviews, artistic criticism, legal reports, financial data, and society affairs that, taken together, produced a constantly changing rendering of publicity and reputation. Soane himself not only read these publications—he subscribed to the

Not all of the attention offered by these publications was favorable. On October 16, 1796, the

derision. The poem’s rhyming couplets sarcastically praised Soane and his new designs for the Bank of England. Belittling comments on his diverse architectural practice—“Glory to thee Great Artist Soul of Taste / For mending pigsties when a plank’s misplaced”—were set alongside hyperbolic epithets deriding the peculiarities of his architectural style and its interpretive development of classical precedent by noting its “pilasters scor ’d like loins of pork” and seeing its “order in confusion move / scrolls fixed below and pedestals above.” The poem ended with the succinct advice: “In silence build from models of Your own / And never imitate the Works of Sxxne.”11 The poem, once published and circulated in this manner, presented a public criticism, quite scathing in its tone, of the outward appearance and aesthetic consequence of Soane’s architecture, and sneering at what it regarded as his pretensions to taste. (

During the course of the eighteenth century, instances of libel had been given greater prominence by the increase in published materials and by the intensity of partisan debate, and legal standards for libel soon accommodated the entire range of public discourse from political dissent to critical reviews. Libel could be charged as a crime or as a tort, and while criminal prosecutions drew much attention, the law courts heard civil suits with considerable and increasing frequency. Common law permitted an evolving conception of libel, without fixed or statutory definition, based upon two constituent criteria: defamation and publicity. Defamation was an injury to an individual’s reputation, which was considered a legal right: “The common law [protects] the good fame, as well as the life, liberty, and property of every man—It considers reputation, not only as one of our pure and absolute rights, but as an outwork which defends, and renders them all valuable.”13 Because only a defamation conveyed to a third party could provide cause for libel, a claim also required evidence that the injurious statement had been published, that it had, even in the most circumscribed sense, been made public. Even with these criteria, though, the changing

circumstances of media and the mutable nature of common law would have meant that a critical statement such as that directed at Soane could not <a id="bookmark3"></a>definitely be known as libel prior to the presentation of legal arguments.

Figure 42.

o

Soane’s designs for the Bank of England, an institution of enormous civic and political importance, could hardly have avoided exciting public comment, particularly in light of their disregard for prevailing architectural conventions. Though a private institution, the bank, due to its issuance of the national debt, occupied a central role in the governance and political economy of Great Britain. Soane’s design for its enormous building in the City of London bore the responsibility of national representation, a responsibility that likely accentuated the severity of the poetical critique.14 Soane chose not to ignore the satirical attack. Nor did he rebut it with a satirical response of his own, a common enough strategy but difficult in this instance because the actual author remained anonymous. Nearly three years passed before he could act, but in 1799 Soane began legal proceedings against surveyor Philip Norris, whom he named as the “Publisher” of “The Modern Goth” and a second, equally disparaging poem. (

prejudice, vilify and disgrace the said J.S. in his profession and to injure his fame, credit and reputation.”15

Under prevailing law, civil prosecution for libel could proceed against published statements about an individual that either impaired his position in society by holding him up to public “scorn and ridicule” or that had “a tendency to injure him in his office, profession, calling, or trade.”16 Soane’s brief aimed precisely at these two standards, claiming that the satirical poems were deliberately intended to embarrass Soane publicly and to damage his professional reputation, as the nature of their publication demonstratively proved:

We may fairly assume that [Soane’s designs] could have been attacked in a more serious way than by an anonymous publication of an abusive poem. All public disquisitions on the subject ought to be fair manly candid criticism, and not beholding a man up as an object of scorn and ridicule, to hunt down in his profession and degrade him in Society. In the first stated libel the language is ransacked for terms of scorn and derision, and Mr. Soane is held out to the Public as a man who has disgraced his Country. . . . As the censure is general the reader is left to presume that the work is execrable in toto.17

During the trial, Edmund Law, the counsel for the defense (who would later, ennobled as Lord Ellenborough, hear the case of 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields), argued that although Soane was indeed an “Architect of great merit,” the bank failed to exemplify his talents. Law proceeded to recite the poem line by line, substantiating each of its stinging slights with a comment on Soane’s design. He aimed to demonstrate that the satirical lines criticized specifically the architecture of the building, concluding that “as a public work, in which the national taste was to some degree involved, criticism ought to be entirely free upon it”; the bank was a “public performance” that, given its flaws, was a reasonable “subject of criticism, and even ridicule, provided that it was done in a fair, and manly, way.”18 Both parties emphasized the nature of the criticism—whether it was fair, manly, or candid—rather than its content, because the motivation of the defamatory statement would be evidence of libel, especially in a case where the truth or falsity of the libel could not be definitively asserted. In the case of “The Modern Goth,” whose very title was an accusation of barbarism, the distinction was measured upon an aesthetic plane, with verses that constructed parallels of architecture and personality: “Come, let me place thee in the foremost rank, / By Dulness, fated to deface the Bank; / By him, whose dulness darken’d every plan, / Thy style shall finish what his style

began.” Was the intention of such lines to dismiss the architecture or to denigrate Soane? The judge admitted in his instructions to the jury “that architecture and all the other arts … were the subjects of fair criticism,” but he advised that the jury consider “whether that might be done … in a Poem, that was to hold up a man to ridicule all his life long.”19 Viewed in a broader perspective, it was up to the jury to consider the liabilities of two accusations of ugliness, one being the claim made by the verses that the architecture of the Bank of England was ugly, the other being the claim of Soane’s brief that the public scorn and ridicule was itself ugly. The jury’s subsequent half hour of deliberation and verdict of not guilty dismissed Soane’s libel suit and settled the proceeding in favor of the permissibility of <a id="bookmark4"></a>the aesthetic critique of his architecture.

Figure 43.

n

But “The Modern Goth” episode would prove to be only the first of Soane’s encounters with defamatory publications. Critical letters, pamphlets, and reviews were attendants to his celebrity, and recourse to law became his instinctive response. During May and June 1821, three essays appeared in the

Novelty.”21 Soane responded at once, attempting to discover the identity of the author and consulting acquaintances on the advisability of bringing suit against the

Very likely, the courts would have considered the

his work.24 The law, in other words, distinguished between character and reputation, the former being the private moral composition of an individual and the latter his public representation, which was, at least in the case of an architect, artist, or writer, subject to public judgment. Lord Ellenborough went on to assert the positive value of such criticism in identifying and suppressing undeserving artistic productions: “It prevents the dissemination of bad taste, by the perusal of trash; and prevents people from wasting both time and money.”25 Here Lord Ellenborough was recapitulating a point he had formulated in 1799 as defense counsel in Soane’s action against Norris, where he had argued that “ridicule, while it was applied to public works ill executed, was of admirable use to mankind; for it operated to keep in the shade unmeaning dulness, instead of her coming forward with her languid spirit and shapeless figure to obtrude herself among the Muses and the Graces.”26

The

submit his own case to the public. Two letters that, given John Taylor’s proprietorship, must have been written with Soane’s assistance or consent soon appeared in the

The publicity surrounding the

erroneous works,” and this regulatory function was all the more vital in the case of an architect, “whose works, like his materials, are lasting, and who covers a metropolis with them.”35

Adding to the obvious injuries inflicted on Soane by the trial—the evidentiary recitation of the libelous text and its reproduction in newspaper accounts, and of course the failure to win a legal defense of his reputation— was the fact that the proceedings were held in a building of his own design, the New Law Courts at Westminster Hall. (

Figure 44.

Sketch of a Design for part of the New Law Courts at Westminster

c

Through the decades-long course of Soane’s several encounters with aesthetic commentary, the judgment of ugliness enacted a precipitating role

rather than a concluding one. His career included successes and failures, and no one of the critical judgments had a fatal repercussion, but they precipitated a sequence of differentiations and identifications bringing the aesthetic register into new relations with circumstances outside of architecture. By prompting what was ultimately a detour through the institutions of the court and through the changing mechanisms of libel law, the judgment of ugliness led to the distinction or separation of aesthetic criticism, to its depersonalization, in a direct sense, and therefore allowed for its layering onto other planes of social transaction, such as the professional or the political. A judgment of beauty, of course, would not have prompted any such recourse to law or seeking of remedy; it was the serial assessments of dullness, distaste, disproportion that pressed the aesthetic toward the legal and thence toward the social. Soane’s scrap-books of newspaper clippings give palpable evidence of his concern for, and his attempt to bring to bear some personal control over, the public sphere made concrete in the ever-accumulating pages of newspapers and journals. The scrapbooks document his broad curiosity in diverse subjects and events, from the Napoleonic Wars to experiments in electricity, and throughout his attention to the cultivation of reputation is clearly evident. Among the clippings can be found dozens of reports of sundry types of libel trials— from defenses of professional competence to defenses of women’s honor— <a id="bookmark6"></a>that clearly suggest a more than abiding interest. (

Figure 45.

e

Criticism

Resolved:

That no comments or criticisms on the opinions or productions of living artists in this Country should be introduced into any lectures given at the Royal Academy.37

On February 11, 1810, a correspondent for the

compositions.”40 Soane, already keenly sensitive to the nature of criticism, was evidently alert to the need for propriety in the institutional context of the Royal Academy, whose members were, by the definition of its charter, to be considered accomplished artists who merited their high reputations.41 On the evening of January 29, 1810, Soane delivered his fourth lecture, on the topic of the relationship between parts and the whole, employing drawings to illustrate his points. Proceeding to a discussion of buildings that failed to resolve into unified form, and as an example of the undesirable practice seen “in many of the buildings of this metropolis” of embellishing one facade at the expense of the others, he placed before his audience two illustrations of the side and rear facades of the recently completed Covent Garden Theatre by the young architect Robert Smirke: “These two drawings of a more recent work point out the glaring impropriety of this defect in a manner if possible still more forcible and more subversive of true taste. The public attention, from the largeness of the building, being

#bookmark7particularly called to the contemplation of this national edifice.”42 (Figures 46 and 47) Soane’s derogation of the architecture of a fellow academician—

m

years earlier—startled his audience, many of whom hissed in protest. Soane had obviously anticipated the effect of his remarks, for he immediately added: “It is extremely painful to me to be obliged to refer to modern works, but if improper models, which become more dangerous from being constantly before us, are suffered, from false delicacy, or other motives, to pass unnoticed, they become familiar, and the task I have undertaken would be not only neglected but the duty of the Professor, as pointed out by the Laws of the Institution, becomes a dead letter.”43 Having thus echoed Lord Ellenborough’s reasoning, he then proceeded to recite once again from the Founding Instrument the “laws of the Institution” that obliged him to offer such criticisms for the edification of the students. Soane intended his two illustrations to show the marked contrast between the front facade, already more simple or grave than many had expected the new theater to be, and the unadorned sides and rear, whose scale and plainness suggested a warehouse rather than a civic building. The omission of adjacent buildings exaggerated the effect of an overwhelming dullness. Motivated by spite toward Smirke as much as by pedagogical intention, Soane’s criticism was by some judged to be the uglier aspect of the affair. The Royal Academy responded quickly to his provocation; within the week, the council met and drafted the

resolution that prohibited any “comments or criticisms on the opinions or productions of living artists in this Country” to be introduced into lectures.44 Soane answered that this unacceptable condition would force him to suspend his course of lectures, but the General Assembly ratified the <a id="bookmark7"></a>council’s resolution nevertheless, with only one member voting in dissent.

Figures 46 and 47.

l

The broad resolution prohibited even “comments” upon any aspect of an artist’s work, whether the actual productions of an artist or his “opinions” expressed in another medium. Obviously intended to maintain a presumed propriety in the affairs of the academy, it resulted in part from some members’ personal antipathy toward Soane. But the resolution was undoubtedly also a reaction against the severe partisan criticism that circulated in newspapers and reviews outside the academy; each year, the annual exhibition exposed individual academicians and the Royal Academy itself to the juridical determinations of the press. In a period before illustrated newspapers and journals, criticism often circulated more widely than the paintings or sculptures it addressed; even architecture, more visible to the course of daily life in London, was depicted textually to a large

audience who remained unacquainted with the actual works.45 The members’ experience of the exhibition reviews undoubtedly swayed many of them in favor of the ban, which promised to maintain the academy as a sanctuary in which one’s “high reputation,” the first of the criteria of membership, would never be impugned.

But while a large group of academicians had reacted adversely to Soane’s comments, others agreed that the instruction of students required such criticisms and expressed their support privately, in correspondence and in social meetings. Soane solicited further sympathy by privately circulating a lengthy pamphlet titled “An Appeal to the Public: Occasioned by the Suspension of the Architectural Lectures in the Royal Academy,” which presented his defense in a didactic brief, with more comments on the Covent Garden Theatre and arguing that criticism was necessary to prevent the propagation of bad taste through poor examples. Public support for Soane’s position appeared in the pages of the

The conflict formally ended in 1813, seemingly through the mutual exhaustion of the antagonists; the Assembly passed a statement regretting that Soane had taken personal offense at a law that was intended to apply

generally, and an appeased Soane recommenced his lectures. But the question of criticism, like the resolution itself, had not been withdrawn. In March 1815, Soane ended the final lecture of his series by quoting the closing lines of Alexander Pope’s 1711

The visibility and presence of architectural ugliness—of the palpable eyesores of the metropolis—conflated and collapsed otherwise differentiated social trajectories, the lives of real persons, the changing standards and predilections of taste, and the evolving legal regulations of common law. In condensing these, architectural ugliness also participated in the novel reconstitution of architect and subjectivity, in effect depersonalizing the sentiments of taste and refashioning them as social instruments, calibrated by conventions of criticism and by mechanisms of libel law. While the most notable judgments may have predictably pertained to buildings of national significance such as Soane’s Bank of England or Smirke’s patent theater in Covent Garden, these were not exceptions, but rather part of a broader assessment of the physical monuments of civic life. When Soane, Smirke, and their contemporary John Nash were appointed

architects to the Board of Works to advise on the building program of the Church Commissioners, they joined an effort to construct a multitude of churches for a minimum outlay of expense. With a budget of no more than twenty thousand pounds per building, the architecture of each was inevitably impoverished to some degree, even as it would just as inevitably be the focus of public scrutiny. One of Nash’s designs, All Souls, Langham Place, received perhaps the most scathing derision in the House of Commons, when Henry Gray Bennet rose to say that “it was deplorable, a horrible object, and never had he seen so shameful a disgrace to the metropolis. It was like a flat candlestick with an extinguisher on it. He saw a great number of churches building, of which it might be said, that one was worse than the other. . . . No man who knew what architecture was, would have put up the edifices he alluded to, and which disgusted every body, while it made every body wonder who could be the asses that had planned, and the fools that had built them.”53 Parliamentary privilege protected Bennet from any potential repercussion—statements made in the House of Commons were exempted from prosecution for slander—but in any case the notable aspect of his obloquy was the explicit absence of Nash’s name, with Bennet wondering who could have been the person responsible for <a id="bookmark8"></a>such architecture.

Figure 48.

e

More curious, and perhaps more perceptive, was the caricature that the incident inspired George Cruikshank to draw. (

The novel constructions of aesthetic criticism formulated through these events and set forward in libel rulings at the beginning of the century gained

substance as legal precedents over the decades. They did not, however, forestall further libel trials, including one of the most famous,

Figure 49.

A

Punch

o

By the middle of the twentieth century, a moment when modernism was becoming widespread but had not secured the broad approbation of public taste, architecture remained susceptible to ridicule in terms not far removed from those familiar to Soane or Nash. The aesthetic and linguistic vocabulary was different, but the judged failing of an architect to recognize a manifest ugliness remained a distillation of critical comment. Architectural critics, by now a recognized profession of their own, diagnosed the difficulty as a distance in understanding between architects and the lay public that corresponded to a distinction between the appearance of a building and the many contextual intricacies of its construction and use. Using the example of the lengthy official debates over the proposed plans for a large new building in Piccadilly Circus, Reyner Banham explained that the “general public was therefore baffled to find that what it thought was simply a straightforward argument about an ugly building seemed to be largely concerned with matters like illuminated advertising in Latin America, underground pedestrian circulation, shopping habits in Coventry … and other matters that seemed not to have even marginal bearing on the appearance of the building.” The solution, he suggested, was to solicit more “responsible and informed criticism from the lay side,” which had disappeared, Banham thought, in Ruskin’s day.56

Along with Banham, a number of architectural journalists and editors in Great Britain expressed their concern that the criticism of architecture was insufficiently rigorous, that it was in fact rarely critical. Beginning in 1948, J. M. Richards, one of the editors of the

however, one practical difficulty to be overcome: the law of libel, which applies more stringently to architecture than to the other arts because of the large amount of someone else’s money involved. . . . In criticizing an architect’s work it is often difficult to draw the line between what is merely an opinion on his merits as a designer and what is an opinion on his competence to handle—or incompetence to mishandle—a client’s or a company’s funds.”57 The continuing confirmation of the standard of libel as requiring the distinction of architect from architecture had, according to Richards, come to forestall the possibility of matching the critical attention that prevailed in other arts. As a remedy, Richards speculated that more “frank architectural criticism” might arise “if there were some system of inviting criticism when a building was completed. . . . Following the precedent of the first night ticket sent to the dramatic critic and the book sent to the reviewer, which were an invitation to criticise.”58 Whether such a process could be installed, and whether it would lead to a new critical freedom, was a question he deferred to “the legal experts.” But without such a process, he predicted a continuation of a harmful mediation of architectural discourse: “Any attempt at seriously criticizing buildings, since it takes on the character of an unwarranted attack, creates a resentful critical climate in which reasonable discussion is most difficult. As elsewhere, the law of libel chiefly operates not when it is really applicable but through the atmosphere of caution it engenders.”59

Though less frequently pursued than in Soane’s day, the threat of libel action has not disappeared from architectural discourse, even today. In late summer 2014, reports that the London-based architect Zaha Hadid was suing the critic Martin Filler for defamation were met with considerable surprise. In an essay titled “The Insolence of Architecture,” ostensibly a book review and published in the

retaliatory lawsuit seemed to startle media audiences more than Filler’s accusations. Why would an architect, secure in her international reputation, resort to a lawsuit to reply to the commentary of an architectural critic? Was not vituperative criticism simply the collateral cost of celebrity in the twenty-first century? Was not her architecture, especially in its most public manifestations, legitimately subject to the scrutiny of media? Such questions are evidence of a contemporary acclimation to the media environment of modern architecture, with the lawsuit received as a seemingly novel challenge to that structure.

The particular transgression in the recent case, according to the architect’s brief, was Filler’s assertion that Hadid had expressed unconcern over the deaths of workers in the construction of her work in Qatar and that she had disowned responsibility (which Filler implied she bore) for those deaths. In addition, the brief stated, Filler had presented an

The surprise with which the case was met—surprise that Filler (or more, his publisher) would have presented such a scathing critique, and surprise

that Hadid would respond with a suit for libel—should in fact have been no surprise at all, for both were predictable continuations of the trajectory along which public criticism and judgments of architectural ugliness were at first linked to and then separated from criticism of individual architects in the novel formulations of English libel law that emerged at the start of the nineteenth century. From those origins, moving along the course of professionalism in which an architect’s reputation assumed the different and more concrete forms of artistic ability

查看更多

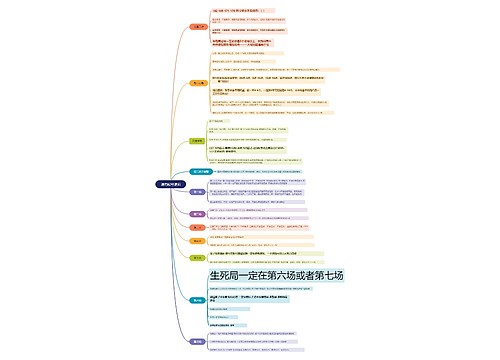

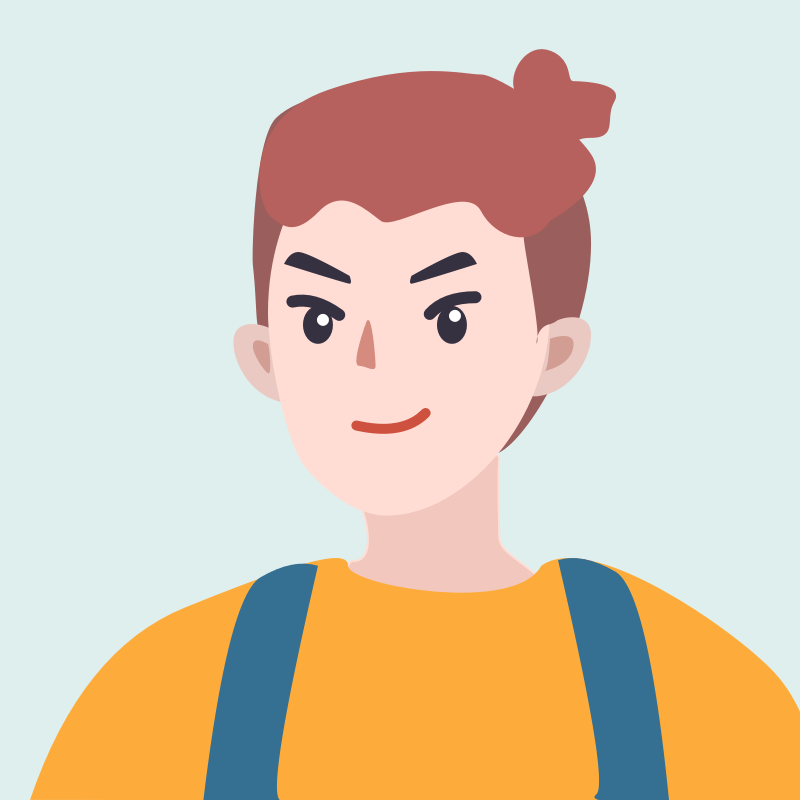

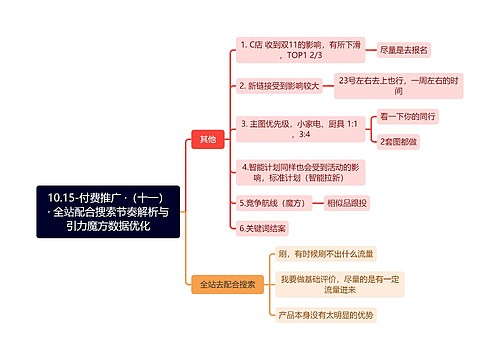

10.15-付费推广 ·(十一)· 全站配合搜索节奏解析与引力魔方数据优化思维导图

U249128194

U249128194树图思维导图提供《10.15-付费推广 ·(十一)· 全站配合搜索节奏解析与引力魔方数据优化》在线思维导图免费制作,点击“编辑”按钮,可对《10.15-付费推广 ·(十一)· 全站配合搜索节奏解析与引力魔方数据优化》进行在线思维导图编辑,本思维导图属于思维导图模板主题,文件编号是:ca82ce4ec961ffd61f0a484a5c579820

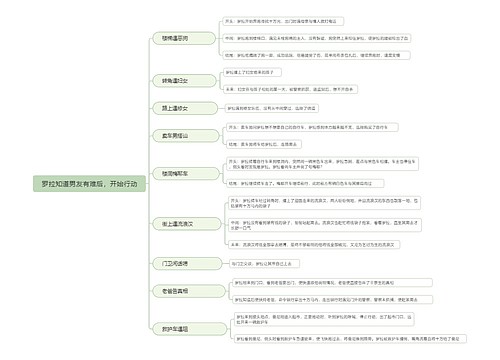

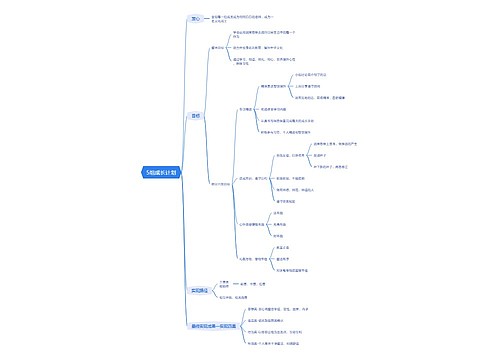

5组成长计划思维导图

U529985218

U529985218树图思维导图提供《5组成长计划》在线思维导图免费制作,点击“编辑”按钮,可对《5组成长计划》进行在线思维导图编辑,本思维导图属于思维导图模板主题,文件编号是:567eeaf1834765b5fd51195a76080718

相似思维导图模版

首页

我的文件

我的团队

个人中心