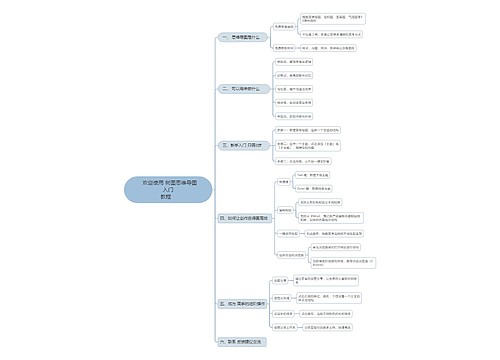

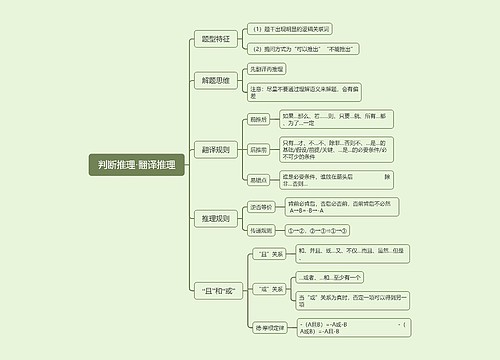

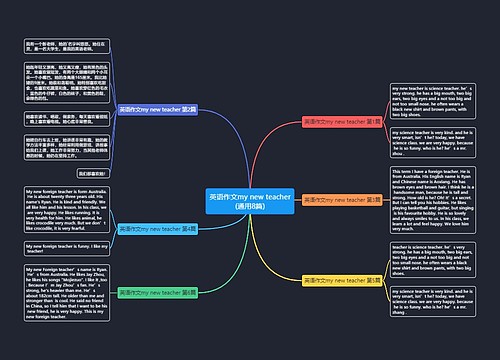

The New Wave of Regionalism思维导图

U349397490

2023-11-03

此类研究

卡岑斯坦

州际

区域主义的新浪潮介绍

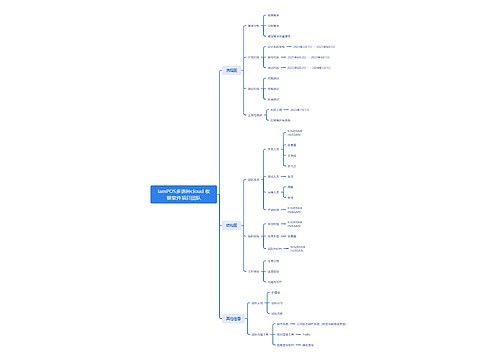

树图思维导图提供《The New Wave of Regionalism》在线思维导图免费制作,点击“编辑”按钮,可对《The New Wave of Regionalism》进行在线思维导图编辑,本思维导图属于思维导图模板主题,文件编号是:c7804b363574bc9c97a2b077382bdcc2

思维导图大纲

相关思维导图模版

The New Wave of Regionalism思维导图模板大纲

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

Edward D. Mansield and Helen V. Milner

Introduction

Economic regionalism appears to be growing rapidly. Why this has occurred and what bearing it will have on the global economy are issues that have generated considerable interest and disagreement. Some observers fear that regional economic institutions—such as the EuropeanUnion (EU), the NorthAmerican Free Trade Agree- ment (NAFTA), Mercosur, and the organization ofAsia-Pacii c Economic Coopera- tion (APEC)—will erode the multilateral system that has guided economic relations since the end of World War II, promoting protectionism and conlict. Others argue that regional institutions will foster economic openness and bolster the multilateral system. This debate has stimulated a large and inluential body of research by econo- mists on regionalism’s welfare implications.

Economic studies, however, generally place little emphasis on the political condi- tions that shape regionalism. Lately, many scholars have acknowledged the draw- backs of such approaches and have contributed to a burgeoning literature that sheds new light on how political factors guide the formation of regional institutions and their economic effects. Our purpose is to evaluate this recent literature.

Much of the existing research on regionalism centers on international trade (al- though efforts have also been made to analyze currency markets, capital lows, and other facets of international economic relations).1 Various recent studies indicate that whether states choose to enter regional trade arrangements and the economic effects of these arrangements depend on the preferences of national policymakers and inter- est groups, as well as the nature and strength of domestic institutions. Other studies focus on international politics, emphasizing how power relations and multilateral

For helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article, we are grateful to David Baldwin, Peter Goure- vitch, Stephan Haggard, Peter J. Katzenstein, David A. Lake, Randall L. Schweller, Beth V. Yarbrough, and three anonymous reviewers. In conducting this research, Mansield was assisted by a grant from the Ohio State University Office of Research and by the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, where he was a National Fellow during 1998–99.

1. On this issue, see Cohen 1997; Lawrence 1996; and Padoan 1997.

International Organization

3

r1999 by The IO Foundation and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

institutions affect the formation of regional institutions,the particular states compos- ing them, and their welfare implications. We argue that these analyses provide key insights into regionalism’s causes and consequences. They also demonstrate the risks associated with ignoring its political underpinnings. At the same time, however, re- cent research leaves various important theoretical and empirical issues unresolved, including which political factors bear most heavily on regionalism and the nature of their effects.

The resolution of these issues is likely to help clarify whether the new ‘‘wave’’ of regionalism will be benign or malign.2 The contemporary spread of regional trade arrangements is not without historical precedent. Such arrangements promoted com- mercial openness during the nineteenth century, but they also contributed to eco- nomic instability throughout the era between World Wars I and II. Underlying many debates about regionalism is whether the current wave will have a benign cast, like the wave that arose during the nineteenth century, or a malign cast, like the one that emerged during the interwar period. Here, we argue that the political conditions surrounding the contemporary episode augur well for avoiding many of regional- ism’s more pernicious effects, although additional research on this topic is sorely needed.

We structure our analysis around four central questions. First, what constitutes a region and how should regionalism be deined? Second, why has the pervasiveness of regional trade arrangements waxed and waned overtime? Third, why do countries pursue regional trade strategies, instead of relying solely on unilateral or multilateral ones; and what determines their choice of partners in regional arrangements? Fourth, what are the political and economic consequences of commercial regionalism?

Regionalism: An Elusive Concept

Extensive scholarly interest in regionalism has yet to generate a widely accepted deinition of it. Almost ifty years ago, Jacob Viner commented that ‘‘economists have claimed to ind use in the concept of an ‘economic region,’but it cannot be said that they have succeeded in inding a deinition of it which would be of much aid . . . in deciding whether two or more territories were in the same economic region. ’’3 Since then, neither economists nor political scientists have made much headway toward settling this matter.4

Disputes over the deinition of an economic region and regionalism hinge on the importance of geographic proximity and on the relationshipbetween economiclows and policy choices. A region is often deined as a group of countries located in the same geographicallyspecii ed area. Exactly which areas constitute regions, however,

2. Bhagwati distinguishes two waves of regionalism since World War II. The irst began in the late 1950s and lasted untilthe 1970s;the second began in the mid-1980s. These waves are discussed at greater length later in this article. See Bhagwati 1993.

3. Viner 1950, 123.

4. On this issue, see Katzenstein 1997a, 8–11.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

remains controversial. Some observers, for example, consider Asia-Pacii c a single region, others consider it an amalgamation of two regions, and still others consider it a combination of more than two regions. Furthermore, a region implies more than just close physical proximity among the constituent states. The United States and Russia, for instance, are rarely consideredinhabitants of the same region, even though Russia’s eastern coast is very close to Alaska. Besides proximity, many scholars insist that members of a common region also share cultural, economic, linguistic, or political ties.5 Relecting this position, Kym Anderson and Hege Norheim note that ‘‘while there is no ideal deinition [of a region], pragmatism would suggest basing the deinition on the major continents and subdividingthem somewhat according to a combination of cultural, language, religious, and stage-of-development criteria. ’’6

Setting aside the issue of how a region should be deined, questions remain about whether regionalism pertains to the concentration of economic lows or to foreign policy coordination. Some analyses deine regionalism as an

In a recent study, Albert Fishlow and Stephan Haggard sharply distinguish be- tween regionalization, which refers to the regional concentration of economic lows, and regionalism, which they deine as a

5. See, for example, Deutsch et al. 1957; Nye 1971; Russett 1967; and Thompson 1973. 6. Anderson and Norheim 1993, 26.

7. For example, Kupchan 1997.

8. Katzenstein 1997a, 7.

9. See, for example, Krugman 1991a; and Frankel, Stein, and Wei 1995. Of course, regionalism may stem from a combination of economic and political forces as well.

10. Fishlow and Haggard 1992. See also Haggard 1997, 48 fn. 1; and Yarbrough and Yarbrough 1997, 160 fn. 1.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

Since much of the contemporary literature on regionalism focuses on PTAs, we will emphasize them in the following analysis.13 Existing studies frequently consider PTAs as a group, rather than differentiating among the various types of these arrange- ments or distinguishingbetween bilateral arrangements and those composed of more than two parties. To cast our analysis as broadly as possible, we do so as well, although some of the institutional variations among PTAs will be addressed later in this article.

Economic Analyses of Regionalism

Much of the literature on regionalism focuses on the welfare implications of PTAs, both for members and the world as a whole. Developed primarily by economists, this research serves as a point of departure for the following analysis, so we now turn to a brief summary of it. Preferential trading arrangements have a two-sided quality, lib- eralizing commerce among members while discriminating against third parties.14 Since such arrangements rarely eliminate external trade barriers, economists con- sider them inferior to arrangements that liberalize trade worldwide. Just how inferior PTAs are hinges largely on whether they are trade creating or trade diverting, a distinction originally drawn by Viner. As he explained:

There will be commodities . . . for which one of the members of the customs

union will now newly import from the other but which it formerly did not import at all because the price of the protected domestic product was lower than the

price at any foreign source plus the duty. This shift in the locus of production as between the two countries is a shift from a high-cost to a low-cost point. . . .

There will be other commodities which one of the members of the customs union will now newly import from the other whereas before the customs union it im-

ported them from a third country, because that was the cheapest possible source

11. See, for example, Bhagwati 1993; Bhagwati and Panagariya 1996, 4–5; de Melo and Panagariya 1993; and Pomfret 1988.

12. See Anderson and Blackhurst 1993; and the sources in footnote 11, above.

13. In what follows, we refer to regional arrangements and PTAs interchangeably, which is consistent with much of the existing literature on regionalism.

14. As de Melo and Panagariya point out, ‘‘because under regionalism preferences are extended only to partners, it is discriminatory. At the same time it represents a move towards freer trade among partners. ’’ de Melo and Panagariya 1993, 4.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

of supply even after payment of the duty. The shift in the locus of production is now not as between the two member countries but as between a low-cost third country and the other, high-cost, member country.15

Viner demonstrated that a customs union’s static welfare effects on members and the world as a whole depend on whether it creates more trade than it diverts. In his words, ‘‘Where the trade-creating force is predominant, one of the members at least must beneit, both may beneit, the two combined must have a net beneit, and the world at large beneits. . . . Where the trade-diverting effect is predominant, one at least of the member countries is bound to be injured, both may be injured, the two combined will suffer a net injury, and there will be injury to the outside world and to the world at large.’’16 Viner also demonstrated that it is very difficult to assess these effects on anything other than a case-by-case basis. Over the past ifty years, a wide variety of empirical efforts have been made to determine whether PTAs are trade creating or trade diverting.As we discuss later, there is widespread consensus that the preferential arrangements forged during the nineteenth century tended to be trade creating and that those established between World Wars I and II tended to be trade diverting;however, there is a striking lack of consensus on this score about the PTAs developedsince WorldWar II.17

15. Viner 1950, 43. For comprehensive overviews of the issues addressed in this section, see Baldwin and Venables 1995; Bhagwati 1991, chap. 5; Bhagwati and Panagariya 1996; Gunter 1989; Hine 1994; and Pomfret 1988.

16. Viner 1950, 44.

17. One reason for the lack of consensus on this issue is the dearth of reliable information about the degree to which price changes induce substitution across imports from different suppliers. Another reason is the difficulty associated with constructing counterfactuals (or ‘‘antimondes’’) that adequately gauge the effects of PTAs. On these issues, see Hine 1994; and Pomfret 1988, chap. 8.

18. Krugman 1991a, 16.

19. See ibid.; and Krugman 1993, 61.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

Consistent with this proposition, a series of simulations by Jeffrey A. Frankel, Ernesto Stein, and Shang-Jin Wei reveal that world welfare is reduced when two or three PTAs exist, depending on the height of the external tariffs of each arrange- ment.20 T. N. Srinivasan and Eric Bond and Constantinos Syropoulos, however, have criticized the assumptions underlying Krugman’s analysis.21 In addition, various ob- servers have argued that the static nature of his model limits its ability to explain how PTAs expand and the welfare implications of this process.22 These debates further relect the difficulty that economists have had drawing generalizations about the welfare effects of PTAs. As one recent survey concludes, ‘‘analysis of the terms of trade effects has tended toward the same depressing ambiguity as the rest of customs union theory. ’’23

A regional trade arrangement can also inluence the welfare of members by allow- ing irms to realize economies of scale. Over three decades ago, Jagdish Bhagwati, Charles A. Cooper and Benton F. Massell, and Harry Johnson found that states could reduce the costs of achieving any given level of import-competing industrialization by forming a PTA within which scale economies couldbe exploited and then discrimi- nating against goods emanating from outside sources.24 Indeed, this motivation con- tributed to the spate ofPTAs establishedby less developed countries(LDCs) through- out the 1960s.25 More recent studies have examined how scale economies within regional arrangements can foster greater specialization and competition and can shift the location of production among members.26 Although these analyses indicate that PTAs could yield economic gains for members and adversely affect third parties, they also underscore regionalism’s uncertain welfare implications 27

Besides its static welfare effects, economists have devoted considerable attention to whether regionalism will accelerate or inhibit multilateral trade liberalization, an issue that Bhagwati refers to as ‘‘the dynamic time-path question.’’28 Several strands of research suggest that regional economic arrangements might bolster multilateral openness. First, Murray C. Kemp and Henry Wan have demonstrated that it is pos- sible for any group of countries to establish a PTA that does not degrade the welfare of either members or third parties, and that incentives exist for the union to expand until it includes all states (that is, until global free trade exists).29 Second, Krugman and Lawrence H. Summers note that regional institutions reduce the number of ac- tors engagedin multilateralnegotiations,thereby muting problems of bargaining and collective action that can hamper such negotiations 30 Third, there is a widespread

20. Frankel, Stein, and Wei 1995.

21. See Bond and Syropoulos1996a; and Srinivasan 1993.

22. See Bhagwati and Panagariya 1996, 47; and Srinivasan 1993.

23. Gunter 1989, 16. See also Baldwin and Venables 1995, 1605.

24. See Bhagwati 1968; Cooper and Massell 1965a,b;and Johnson 1965.

25. Bhagwati 1993, 28.

26. See,for example, Krugman 1991b;and Padoan 1997, 108–109.

27. See Baldwin and Venables 1995, 1605–13; and Gunter 1989, 16–21.

28. See Bhagwati 1993; and Bhagwati and Panagariya 1996.

29. Kemp and Wan 1976.

30. See Krugman 1993; and Summers 1991.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

beliefthat regional trade arrangements can induce members to undertake and consoli- date economic reforms and that these reforms are likely to promote multilateral open- ness.31

However, clear limits also exist on the ability of regional agreements to bolster multilateralism. Bhagwati, for example, maintains that although the Kemp-Wan theo- rem demonstrates that PTAs could expand until free trade exists, this result does not specify the likelihood of such expansion or that it will occur in a welfare-enhancing way.32 In addition, Bond and Syropoulos argue that the formation of customs unions may render multilateral trade liberalization more difficult by undercutting multilat- eral enforcement.33 But Kyle Bagwell and Robert Staiger show that PTAs have con- tradictory effects on the global trading system. They claim that ‘‘the relative strengths of these . . . effects determine the impact of preferential agreement on the tariff struc- ture under the multilateral agreement, and . . . preferential trade agreements can be either good or bad for multilateral tariff cooperation, depending on the param- eters.’’34 They do conclude, however, that ‘‘it is precisely when the multilateral sys- tem is working poorly that preferential agreements can have their most desirable effects on the multilateral system. ’’35

Economic analyses indicate that regionalism’s welfare implications have varied starkly over time and across PTAs. As Frankel and Wei conclude, ‘‘regionalism can, depending on the circumstances, be associated with either more or less general liber- alization.’’36 In what follows, we argue that these circumstances involve political conditions that economic studies often neglect. Regionalism can also have important political consequences, and they, too, have been given short shrift in many economic studies. Lately, these issues have attracted growing interest, sparking a burgeoning literature on the political economy of regionalism. We assess this literature after conducting a brief overview of regionalism’s historical evolution.

Regionalism in Historical Perspective

Considerable interest has been expressed in how the preferential economic arrange- ments formed after World War II have affected and will subsequently inluence the global economy. We focus primarily on this era as well; however, it is widely recog- nized that regionalism is not just a recent phenomenon. Analyses of the current spate of PTAs often draw on historical analogies to prior episodes of regionalism. Such analogies can be misleading because the political settings in which these episodes arose are quite different from the current setting. To develop this point, it is useful to

31. See, for example, Lawrence 1996; and Summers 1991.

32. Bhagwati 1991, 60–61; and 1993.

33. Bond and Syropoulos1996b.

34. Bagwell and Staiger 1997, 27.

35. Ibid., 28.

36. Frankel and Wei 1998, 216.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

begin by describing each of the four waves of regionalism that have arisen over the past two centuries.

The initial episode occurred during the second half of the nineteenth century and was largely a European phenomenon.37 Throughout this period, intra-European trade both rose dramatically and constituted a vast portion of global commerce.38 More- over, economic integration became sufficiently extensive that, by the turn of the twentieth century, Europe had begun to function as a single market in many re- spects.39 The industrial revolution and technological advances attendant to it that facilitated interstate commerce clearly had pronounced effects on European integra- tion;but so did the creation of various customs unions and bilateral trade agreements. Besides the well-known German Zollverein, the Austrian states established a cus- toms union in 1850, as did Switzerland in 1848, Denmark in 1853, and Italy in the 1860s. The latter coincided with Italian statehood, not an atypical impetus to the initiation of a PTA in the nineteenth century. In addition, various groups of nation- states forged customs unions, including Sweden and Norway and Moldavia and Wal- lachia.40

The development of a broad network of bilateral commercial agreements also contributed to the growth of regionalism in Europe. Precipitated by the Anglo- French commercial treaty of 1860, they were linked by unconditional most-favored- nation (MFN) clauses and created the bedrock of the international economic system until the depression in the late nineteenth century.41 Furthermore, the desire by states outside this commercial network to gain greater access to the markets of participants stimulated its rapid spread. As of the irst decade of the twentieth century, Great Britain had concludedbilateral arrangements with forty-six states, Germany had done so with thirty countries, and France had done so with more than twenty states.42 These arrangements contributed heavily to the unprecedented growth of European integration and to the relatively open international commercial system that character- ized the latter half of the nineteenth century, underpinning what Douglas A. Irwin refers to as an era of ‘‘progressive bilateralism. ’’43

World War I disrupted the growth of regional trade arrangements. But a second wave of regionalism, which had a decidedly more discriminatory cast than its prede- cessor, began soon after the war ended. The regional arrangements formed between

37. See, for example, Kindleberger 1975; and Pollard 1974. However, regionalism was not conined solely to Europe during this era. Prior to 1880, for example, India, China, and Great Britain comprised a ‘‘tightly-knit trading bloc’’ in Asia. Afterward, Japan’s economic development and its increasing political power led to key changes in intra-Asian trade patterns. Kenwood and Lougheedreport that ‘‘Asia replaced Europe and the United States as the main source of Japanese imports, supplying almost one-half of these needs by 1913. By that date Asia had also become Japan’s leading regional export market.’’ Kenwood and Lougheed 1971, 94–95.

38. Pollard 1974, 42–51, 62–66.

39. Kindleberger 1975; and Pollard 1974. Of course, trade grew rapidly worldwide during this era, but the extent of its growth and of economic integration was especially marked in Europe.

40. See Irwin 1993, 92; and Pollard 1974, 118.

41. See,for example, Irwin 1993; Kenwood and Lougheed 1971; and Pollard 1974. 42. Irwin 1993, 97.

43. Ibid., 114. See also Pollard 1974, 35.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

World Wars I and II tended to be highly preferential. Some were created to consoli- date the empires of major powers, including the customs union France formed with members of its empire in 1928 and the Commonwealth system of preferences estab- lished by Great Britain in 1932.44 Most, however, were formed among sovereign states. For example, Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia, and Bulgaria each negotiated tariff preferences on their agricultural trade with various European countries. The Rome Agreement of 1934 led to the establishment of a PTA involving Italy, Austria, and Hungary. Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden concluded a series of economic agreements throughout the 1930s. Ger- many also initiated various bilateral trade blocs during this era. Outside of Europe, the United States forged almost two dozen bilateral commercial agreements during the mid-1930s, many of which involved Latin American countries.45

Longstanding and unresolved debates exist about whether regionalism deepened the economic depression of the interwar period and contributed to political tensions culminating in World War II.46 Contrasting this era with that prior to World War I, Irwin presents the conventional view: ‘‘In the nineteenth century, a network of trea- ties containing the most favored nation (MFN) clause spurred major tariff reductions in Europe and around the world, [ushering] in a harmonious period of multilateral free trade that compares favorably with . . . the recent GATT era. In the interwar period, by contrast, discriminatory trade blocs and protectionist bilateral arrange- ments contributed to the severe contraction of world trade that accompanied the Great Depression.’’47 The latter wave of regionalism is often associated with the pursuit of beggar-thy-neighbor policies and substantial trade diversion, as well as heightened political conlict.

Scholars frequently attribute the rise of regionalism during the interwar period to states’ inability to arrive at multilateral solutions to economic problems. As A. G. Kenwood and A. L. Lougheed note, ‘‘The failure to achieve international agreement on matters of trade and inance in the early 1930s led many nations to consider the alternative possibility of trade liberalizing agreements on a regionalbasis.’’48 In part, this failure can be traced to politicalrivalries among the major powers and the use of regional trade strategies by these countries for mercantilist purposes.49 Hence, al- though regionalism was not new, both the political context in which it arose and its consequences were quite different than before WorldWar I.

44. Pollard 1974, 145.

45. On the commercial arrangements discussed in this paragraph, see Condliffe 1940, chaps. 8–9; Hirschman [1945]1980;Kenwood and Lougheed1971,211–19; and Pollard1974,49.Although our focus is on commercial regionalism, it should be noted that the interwar era was also marked by the existence of at least ive currency regions. For an analysis of the political economy of currency regions, see, for example, Cohen 1997.

46. See, for example, Condliffe 1940, especially chaps. 8–9; Hirschman [1945] 1980; Kindleberger 1973; and Oye 1992.

47. Irwin 1993,91. He notes that these generalizations are somewhat inaccurate, as doEichengreen and Frankel 1995. But both studies conirm that regionalism had different effects during the nineteenth cen- tury, the interwar period, and the present; and both view regionalism in the interwar period as most malign.

48. Kenwood and Lougheed 1971, 218.

49. See Condliffe 1940; Eichengreen and Frankel 1995, 97; and Hirschman [1945] 1980.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

Regionalism Since World War II

Since WorldWar II, states have continued to organize commerce on a regional basis, despite the existence of a multilateral economic framework. To analyze regional- ism’s contemporary growth, some studies have assessed whether trade lows are becoming increasingly concentrated within geographically specii ed areas. Others have addressed the extent to which PTAs shape trade lows and whether their inlu- ence is rising. Still others have examined whether the rates at which PTAs form and states join them have increased over time. In combination, these studies indicate that commercial regionalism has grown considerably over the past ifty years.

As shown in Table 1—which presents data used in three inluential studies of regionalism—the regional concentration of trade lows generally has increased since the end ofWorldWar II.50 Much of this overall tendency is attributable to rising trade within Western Europe—especially among parties to the EC—and within East Asia. Some evidence of an upward drift in intraregional commerce also exists within the Andean Pact, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), and between Australia and New Zealand, although outside of the former two groupings, intraregional trade lows have not grown much among developing countries.

One central reason why trade is so highly concentratedwithin many regions is that states located in close proximity often participate in the same PTA.51 That the effects of various PTAs on commerce have risen over time constitutes further evidence of regionalism’s growth.52 As the data in Table 1 indicate, the inluence of PTAs on trade lows has been far from uniform. Some PTAs, like the EC, seem to have had a profound effect, whereas others have had little impact.53 But the data also indicate that, in general, trade lows have tended to increase over time among states that are members of a PTA and not merely located in the same geographic region, suggesting that policy choices are at least partly responsible for the rise of regionalism since WorldWar II.

East Asia, however, is an interesting exception. Virtually no commercial agree- ments existed among East Asian countries prior to the mid-1990s, but rapid eco- nomic growth throughout the region contributed to a dramatic increase in intra- regional trade lows.54 In light ofAsia’s recent inancial crisis, it will be interesting to see whether the process of regionalization continues. Severe economic recession

50. These deine regionalism in somewhat different ways. Anderson and Norheim examine broad geo- graphic areas, de Melo and Panagariya analyze PTAs, and Frankel, Stein, and Wei consider a combination of geographic zones and PTAs. See Anderson and Norheim 1993; de Melo and Panagariya 1993; and Frankel, Stein, and Wei 1995.

51. On the effects of PTAs on trade lows, see, for example, Aitken 1973; Frankel 1993; Frankel, Stein, and Wei 1995; Linnemann 1966; Mansield and Bronson 1997; Tinbergen 1962; and Winters and Wang 1994.

52. See,for example, Aitken 1973; Frankel 1993; and Frankel, Stein, and Wei 1995.

53. Note, however, that some PTAs—especially Mercosur—have had a large effect on trade since 1990. Their effects are not captured in Table 1. We are grateful to Stephan Haggard for bringing this point to our attention.

54. See Anderson and Blackhurst 1993, 8; Frankel 1993; Frankel, Stein, and Wei 1995; and Saxon- house 1993.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

TABLE 1 .

Intraregional

trade小ows

during

the

post-World

War

II

era

A.

Intraregional

trade

divided

by

total

trade

of

each

region

Region

1965

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

East Asia 0.199 0.198 0.213 0.229 0.256 0.293

Western Hemisphere 0.315 0.311 0.309 0.272 0.310 0.285

European Community 0.358 0.397 0.402 0.416 0.423 0.471

European Free Trade Area 0.080 0.099 0.104 0.080 0.080 0.076

Mercosur 0.061 0.050 0.040 0.056 0.043 0.061

Andean Pact 0.008 0.012 0.020 0.023 0.034 0.026

North American Free Trade 0.237 0.258 0.246 0.214 0.274 0.246

Agreement

B.

Intraregionalmerchandise

exports

divided

by

total

merchandise

exports

of

each

region

Region

1948

1958

1968

1979

1990

Western Europe 0.430 0.530 0.630 0.660 0.720

Eastern Europe 0.470 0.610 0.640 0.540 0.460

North America 0.290 0.320 0.370 0.300 0.310

SouthAmerica 0.200 0.170 0.190 0.200 0.140

Asia 0.390 0.410 0.370 0.410 0.480

Africa 0.080 0.080 0.090 0.060 0.060

Middle East 0.210 0.120 0.080 0.070 0.060

World 0.330 0.400 0.470 0.460 0.520

C.

Intraregional

exports

divided

by

total

exports

of

each

region

Region

1960

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

European Community 0.345 0.510 0.500 0.540 0.545 0.604

European Free Trade Area 0.211 0.280 0.352 0.326 0.312 0.282

Association of Southeast Asian Nations 0.044 0.207 0.159 0.169 0.184 0.186

Andean Pact 0.007 0.020 0.037 0.038 0.034 0.046

Canada–United States Free Trade Area 0.265 0.328 0.306 0.265 0.380 0.340

Central American Common Market 0.070 0.257 0.233 0.241 0.147 0.148

Latin American Free Trade Association/ 0.079 0.099 0.136 0.137 0.083 0.106

Latin American Integration Association

Economic Community ofWest African N/A 0.030 0.042 0.035 0.053 0.060

States

Preferential Trading Area for Eastern and N/A 0.084 0.094 0.089 0.070 0.085

SouthernAfrica

Australia–New Zealand Closer Economic 0.057 0.061 0.062 0.064 0.070 0.076

Relations Trade Agreement

Source:

D

Note:

N

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

within Asia concurrent with robust growth in North America and Western Europe may redirect trade lows across regions. This case illustrates the need we described earlier to distinguishbetween policy-inducedregionalism and that stemming primar- ily from economic forces. How important the Association of Southeast Asian Na- tions (ASEAN) and other policy initiatives are in directing commerce shouldbecome clearer as the economic crisis in Asia unfolds.

Also indicative of regionalism’s growth are the increasing rates at which PTAs formed and states joined them throughout the post–World War II period.55 Figure 1 reports the number of regional trading arrangements notiied to the General Agree- ment on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) from 1948 to 1994. Clearly, the frequency of PTA formation has luctuated. Few were established during the 1940s and 1950s, a surge in preferential agreements occurred in the 1960s and 1970s, and the incidence ofPTA creation again trailed off in the 1980s.56 But there has been a signiicant rise in such agreements during the 1990s; and more than 50 percent of all world commerce is currently conducted within PTAs.57 Indeed, they have become so pervasive that all but a few parties to the World Trade Organization (WTO) now belong to at least one.58

Regionalism, then, seems to have occurred in two waves during the post–World War II era. The irst took place from the late 1950s through the 1970s and was marked by the establishment of the EEC, EFTA, the CMEA, and a plethora of re- gional trade blocs formed by developing countries. These arrangements were initi- ated against the backdrop of the Cold War, the rash of decolonization following World War II, and a multilateral commercial framework, all of which colored their economic and political effects. Various LDCs formed preferential arrangements to reduce their economic and political dependence on advanced industrial countries. Designed to discourage imports and encourage the development of indigenous indus- tries, such arrangements fostered at least some trade diversion.59 Moreover, many of them were beset by considerable conlict over how to distribute the costs and beneits stemming from regional integration, how to compensate distributional losers, and how to allocate industries among members.60 Similarly, the CMEA represented an attempt by the Soviet Union to promote economic integration among its political allies, foster the development of local industries, and limit economic dependence on the West. Ultimately, it did little to enhance the welfare of participants.61 In contrast, the regional arrangements concluded among developed countries—especially those in Western Europe—are widely viewed as trade-creating institutions that also contrib- uted to political cooperation.62

55. Mansield 1998.

56. See also de Melo and Panagariya 1993, 3.

57. Serra et al. 1997, 8, ig. 2.

58. World Trade Organization 1996, 38, and 1995.

59. For example, Pomfret 1988, 138.

60. See Bhagwati 1993; and Foroutan 1993.

61. Indeed, some scholars have gone so far as to characterize the CMEA as trade destroying. See, for example, Pomfret 1988, 94–95, 143.

62. For analyses of trade creation and trade diversion in Europe, see Eichengreen and Frankel 1995; Frankel and Wei 1998; and Pomfret 1988, 128–35.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

FIGURE 1 .

The

number

of

preferential

trading

arrangements

noti小ed

to

the

GATT,

1948–94.

The most recent wave of regionalism has arisen in a different context than earlier episodes. It emerged in the wake of the Cold War’s conclusion and the attendant changes in interstate power and security relations. Furthermore, the leading actor in the international system (the United States) is activelypromoting and participatingin the process. PTAs also have been used with increasing regularity to help prompt and consolidate economic and political reforms in prospective members, a rarity during prior eras. And unlike the interwar period, the most recent wave of regionalism has been accompanied by high levels of economic interdependence, a willingness by the major economic actors to mediate trade disputes, and a multilateral(that is, the GATT/ WTO) framework that assists them in doing so and that helps to organize trade relations.63 As Robert Z. Lawrence notes,

The forces driving the current developments differ radically from those driving previous waves of regionalism in this century. Unlike the episode of the 1930s, the current initiatives represent efforts to facilitate their members’ participationin the world economy rather than their withdrawal from it. Unlike those in the

1950s and 1960s, the initiatives involving developing countries are part of a

strategy to liberalize and open their economies to implement export- and foreign- investment-led policies rather than to promote import substitution 64

63. Perroni and Whalley 1996.

64. Lawrence 1996, 6. On the differences between regionalism in the 1930s and in the contemporary era, see also Eichengreen and Frankel 1995; Oye 1992; and Pomfret 1988.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

Our brief historical overview indicates that regionalism has been an enduring fea- ture of the international political economy, but both its pervasiveness and cast have changed overtime. We argue that domestic and international politics are central to explaining such variations as well as the origins and nature of the current wave of regionalism. In what follows, we present a series of politicalframeworks for address- ing these issues and raise some avenues for further research.

Domestic Politics and Regionalism

Although it is frequently acknowledged that political factors shape regionalism, sur- prisingly few systematic attempts have been made to address which factors most fully determine why states choose to pursue regional trade strategies and the precise nature of their effects. Early efforts to analyze the political underpinnings of region- alism were heavily inluenced by ‘‘neofunctionalism.’’65 Joseph S. Nye points out that ‘‘what these studies had in common was a focus on the ways in which increased transactions and contacts changed attitudes and transnational coalition opportunities, and the ways in which institutions helped to foster such interaction.’’66 Lately, ele- ments of neofunctionalism have been revived, especially in research on European integration. Many such analyses concludethat increased economic lows among mem- bers of the EU have changed the preferences of domestic actors, leading them to press for policies andinstitutions that promote deeper integration 67

Societal Factors

As neofunctional studies indicate, the preferences and politicalinluence of domestic groups can affect why regional strategies are selected and their likely economic con- sequences. Regional trade agreements discriminate against third parties, yielding rents for certain domestic actors who may constitute a potent source of support for a PTA’s formation and maintenance.68 Industries that could ward off competitors lo- cated in third parties or expand their share of international markets if they were covered by a PTA have obvious reasons to press for its establishment.69 So do export- oriented industries that stand to beneit from the preferential access to foreign mar- kets afforded by a PTA. In addition, though it is all but impossible to construct a PTA that would not adversely affect at least some politically potent sectors, it is often

65. See, for example, Deutsch et al. 1957; Haas 1958; and Nye 1971.

66. Nye 1988, 239.

67. For example, Sandholtz and Zysman argue that the 1992 project in Europe to ‘‘complete the in- ternal market’’ resulted from a conluence of leadership by the European Commission and pressure from a transnational coalition of business in favor of a European market. Frieden advances a similar argument in explaining supportforthe European Monetary Union, stressing the salience ofthe preferences of European- oriented business and inancial actors. Moravcsik also views the origins of European integration as re- siding in the pressures exerted by European irms and industries with an external orientation for the creation of a larger market. See Sandholtzand Zysman 1989; Frieden 1991; and Moravcsik 1998.

68. See Gunter 1989, 9; and Hirschman 1981.

69. For example, Haggard 1997.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

possible to exclude them from the arrangement, a tack, for example, that led to ‘‘the European Economic Community’s exclusion of agriculture (and, in practice, steel and many other goods), the Caribbean Basin Initiative’s exclusion of sugar, and ASEAN’s exclusion of just about everything of interest. ’’70

Regional trade strategies, therefore, hold some appeal for public officials who need to attract the support of both import-competing and export-oriented sectors. The domestic political viability of a prospective PTA, the extent to which it will create or divert trade, and the range of products it will cover hinge partly on the preferences of and the inluence wielded by key sectors in each country as well as the particular set of countries that can be assembled to participate in it. Unfortunately, existing studies offer relatively few theoretical or empirical insights into these issues, although some recent progress has been made on this front.

Public officials must strike a balance between promoting a country’s aggregate economic welfare and accommodating interest groups whose support is needed to retain office. Gene M. Grossman and Elhanan Helpman argue that whether a country chooses to enter a regional trade agreement is determined by how much inluence different interest groups exert and how much the government is concerned about voters’ welfare.71 They demonstrate that the political viability of a PTA often de- pends on the amount of discrimination it yields. Agreements that divert trade will beneit certain interest groups while creating costs borne by the populace at large. If these groups have more political clout than other segments of society, then a PTA that is trade diverting stands a better chance of being established than one that is trade creating.72 Grossman and Helpman also ind that by excluding some sectors from a PTA, governments can increase the domestic support for it, thus helping to explain why many PTAs do not cover politically sensitive industries. Consistent with earlier research, their results imply that trade-diverting PTAs will face fewer political ob- stacles than trade-creating ones.73 If so, using preferential arrangements as building blocks to support multilateral liberalization will require surmounting substantial do- mestic impediments.

Opinion is divided over the ease with which this can be accomplished. KennethA. Oye argues that discriminatory PTAs can actually lay the basis for promoting multi- lateral openness, especially if the international trading system is relatively closed.74 In his view, discrimination stemming from a preferential arrangement can mobilize and strengthen the political hand of export-oriented (and other antiprotectionist)in- terests located in third parties, thereby generating domestic pressure in these states for agreements that expand their access to PTA members’markets. Such agreements, in turn, are likely to contribute to international openness. However, Anne O. Krueger maintains that the formation and expansion of PTAs may dampen the support of exporters for broader liberalization. As she puts it, ‘‘For those exporters who would

70. Eichengreen and Frankel 1995, 101.

71. Grossman and Helpman 1995, 668; and 1994.

72. Grossman and Helpman 1995, 681. See also Pomfret 1988, 190.

73. For example, Hirschman 1981, 271.

74. Oye 1992, 6–7, 143–44.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

support free trade, the value of further multilateral trade liberalizationis diminished with every new entrant into a preferential trade arrangement, so that exporters’ sup- port for multilateral liberalization is likely to diminish as vested interests proiting from trade diversionincrease.’’75 Hence, it is not clear whether exporters will support regionalism instead of or in addition to multilateralliberalization.

Equally unclear is why exporters would prefer to liberalize trade on a regional rather than a multilateralbasis in the irst place. One possibility is that exporters will be more likely to support regional strategies if they operate in industries character- ized by economies of scale, since, by protecting these sectors from foreign competi- tion and broadening their market access, the formation of a PTA can bolster their competitiveness. Indeed, Milner argues that irms in such industries may be key proponents of regional, rather than unilateral or multilateral, trade policies.76 But because PTAs also liberalize trade among participants, irms with competitors in prospective member countries may seek to bar these states from entering an arrange- ment or oppose its establishment altogether.

Though research stressing the effects of societal factors on regionalism offers vari- ous useful insights, it also suffers from at least two drawbacks. First, there is a lack of empirical evidence indicating which domestic groups support regional trade agree- ments, whose interests these agreements serve, and why particular groups prefer regional to multilateral liberalization. For example, Oye maintains that discrimina- tory arrangements piqued the interest of exporters, and Milner claims that exporters— particularly those with large scale economies—may have favored and gained from NAFTA.77 Neither, however, demonstrates that exporters preferred regional arrange- ments to multilateral ones. Regional liberalization may have been what they had to settle for given the existence of strong, opposing domestic interests. Second, we know little about whether, once in place, regional arrangements foster domestic sup- port for broader, multilateral trade liberalization or whether they undermine such support. These issues offer promising avenues for future research.

Domestic Institutions

In the inal analysis, the decision to enter a PTA is made by policymakers. Both their preferences and the nature of domestic institutions conditionthe inluence of societal actors on trade policy as well as independentlyaffecting whether states elect to em- bark on regional trade initiatives. Of course, policymakers and politically potent societal groups sometimes share an interest informing a PTA. Many regional trade arrangements that LDCs established during the 1960s and 1970s, for instance, grew out of import-substitutionpolicies that were actively promoted by policymakers and strongly supported by various segments of society.78

75. Krueger 1997, 19 fn. 27.

76. Milner 1997. See also Busch and Milner 1994.

77. See Milner 1997; and Oye 1992.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

However, PTAs also have been created by policymakers who preferred to liberal- ize trade but faced domestic obstacles to doing so unilaterally. In this vein, Barry Eichengreen and Jeffrey A. Frankel point out that ‘‘Columbia and Venezuela decided in November 1991 to turn the previously moribund Andean Pact into what is now one of the world’s most successful FTAs. Policymakers in these countries explain their decision as a politically easy way to dismantle protectionistbarriers to an extent that their domestic legislatures would never have allowed had the policy not been pursued in a regional context.’’79 Even if inluentialdomestic actors oppose commer- cial liberalization altogether, institutional factors sometimes create opportunities for policymakers to sidestep such opposition by relying on regional or bilateral trade strategies. Consider the situation Napoleon III faced on the eve of the Anglo-French commercial arrangement. Anxious to liberalize trade with Great Britain, he encoun- tered a French legislature and various salient domestic groups that were highly pro- tectionist. But although the legislature had considerable control over unilateral trade policy, the constitution of 1851 permitted the emperor to sign international treaties without this body’s approval. Napoleon, therefore, was able to skirt well-organized protectionist interests much more easily by concluding a bilateral commercial agree- ment that would have been impossible had he relied solely on unilateral instru- ments.80

Similarly, governments that propose a program of liberal economic reforms and encounter (or expect to encounter) domestic opposition may enter a PTA to bind themselves to these changes.81 Mexico’s decision to enter NAFTA, for example, is frequently discussed in such terms. As one recent study concludes, ‘‘NAFTA should be understood as a commitment device . . . , [which] combined with the inluence of new elites that beneit from export promotion, greatly increases the likelihood that trade liberalizationin Mexico will not be derailed.’’82 For a state that is interested in making liberal economic reforms, the attractiveness of locking them in through an external mechanism, such as joining a PTA, is likely to grow if inluential segments of society oppose reforms and if domestic institutions render policymakers espe- cially susceptible to societal pressures. Under these conditions, however, govern- ments must have the institutionalmeans to circumvent domestic opposition in order to enter such agreements, and the costs of violating a PTA must be high enough to ensure that reforms will not be abrogated.

Although governments may choose to join regional agreements to promote domes- tic reforms, they may also do so if they resist reforms but are anxious to reap the beneits stemming from preferential access to other members’markets. Existing mem- bers of a preferential grouping may be able to inluence the domestic economic

79. Eichengreen and Frankel 1995, 101.

80. See Irwin 1993, 96; and Kindleberger 1975, 39–40. Moreover, this is not an isolated case. Irwin notes that ‘‘Commercial agreements in the form of foreign treaties proved useful in circumventing protec- tionist interests in the legislature throughoutEurope.’’ Irwin 1993, 116 fn. 7.

81. See de Melo, Panagariya, and Rodrik 1993; Haggard 1997; Summers 1991; and Whalley 1998.

82. Tornell and Esquivel 1997, 54. See also Whalley 1998, 71–72. That this arrangement helped to consolidate Mexican economic reforms probably heightened its desirability from the standpoint of the United States and Canada as well. See, for example, Eichengreen and Frankel 1995, 101.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

Using PTA membership to stimulate liberal economic and political reforms is a distinctive feature of the latest wave of regionalism. That these reforms have been designed to open markets and promote democracy may help to account for the rela- tively benign character of the current wave. Underlying demands for democratic reform are fears that admitting nondemocratic countries might undermine existing PTAs composed of democracies and the belief that regions composed of stable de- mocracies are unlikely to experience hostilities. Both views remain open to question. But if entering a preferential arrangement actually promotes the consolidation of liberal economic and politicalreforms and mutes the economic and politicalinstabil- ity that often accompanies such reforms, then the contemporary rise of regionalism may contribute to both commercial openness and political cooperation.87

At the same time, the political viability of such PTAs, the credibility of the institu- tional changes they prompt, and the effect of these arrangements on international openness and cooperation depend heavily on the preferences of powerful domestic groups. Whereas domestic analyses of regionalism have generally focused on either

83. Winters 1993, 213.

84. Birch 1996, 186.

86. Eichengreen and Frankel 1995, 103.

87. On these issues, see Haggard and Kaufman 1995;Haggard and Webb 1994; Lawrence 1996; Mans- ield and Snyder 1995; and Remmer 1998.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

societal or institutionalfactors, more attention needs to be centered on how the inter- action between these factors inluences whether and when countries enter a regional arrangement as well as on the political and economic consequences of doing so.88 Greater attention also needs to be focused on why state leaders have displayed a particular preference for entering regional trade arrangements. One possibilityis that they do so to liberalize trade when faced with domestic obstacles to reducing trade barriers on a unilateral or multilateral basis. Theories outlining the conditions under which leaders prefer to liberalize commerce in theirst place, however, remain scarce.

Furthermore, the extent to which PTAs have been used as instruments for stimulat- ing economic and political liberalization during the current wave of regionalism is quite unusual by historical standards. Chile, for example, withdrew from the Andean Pact in 1976 because it wanted to complete a series of economic reforms that this arrangement prohibited.89 Moreover, attempts to spur democratizationin prospective PTA members are largely unique to the contemporary wave. As noted earlier, the recent tendency of existing PTAs to demand that nondemocratic states complete politicalreforms prior to accession probablyrelects the growing number of preferen- tial arrangements composed of democracies and the widely held beliefby policymak- ers in these regional groupings that fostering democracy will promote peace and prosperity. Nonetheless, we lack a sufficient theoretical understanding of the condi- tions under which PTA membership is used to prompt liberalizing reforms and the factors affecting the success of such efforts.

A related line of research suggests that the similarity of states’politicalinstitutions inluences whether they will form a preferential arrangement and its efficacy once established. Many scholars view a region as implying substantialinstitutionalhomo- geneity among the constituent states. Likewise, some observers maintain that the feasibility of creating a regional agreement depends on prospective members having relatively similar economic or political institutions.90 If trade liberalization requires harmonization in a broad sense, such as in the Single European Act, then the more homogeneous are members’ national institutions, the easier it may be for them to agree on common regionalpolicies andinstitutions. Others point out that countries in close geographic proximity have much less impetus to establish regional arrange- ments if their politicalinstitutions differ signiicantly. In Asia, for example, the scar- city of regional trade arrangements is partly attributable to the wide variation in the constituent states’ political regimes, which range from democracies like Japan to autocracies like Vietnam and China.91

As the initial differences in states’ institutions become more pronounced, so do both the potential gains from and the impediments to concluding a regional agree- ment. Consequently, the degree of institutionalsimilarity among states and the pros- pect that membership in a regional arrangement will precipitate institutional change

88. For one study of this sort, see de Melo, Panagariya, and Rodrik 1993.

90. For example,ibid.

91. Katzenstein 1997a.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

in these states may bear heavily on whether they form a PTA.92 The extant literature, however, provides little guidance about how large institutional differences can be before regionalintegrationbecomes politicallyinfeasible. Nor does it indicate whether regional agreements can help members to lock in institutionalreforms if there is little preexisting domestic support for these changes.

International Politics and Regionalism

The decision to form a PTA rests partly on the preferences and political power of various segments of society, the interests of state leaders, and the nature of domestic institutions. In the preceding section, we suggested some ways that these factors might operate separately and in combination to inluence whether states pursue re- gional trade strategies and regionalism’s economic consequences. But states do not make the decision to enter a PTA in an international political vacuum. On the con- trary, interstate power and security relations as well as multilateral institutions have played key roles in shaping regionalism. Equally important is how regionalism af- fects patterns of conlict and cooperation among states. We now turn to these issues.

Political

Power,

Interstate

Con小ict,

and

Regionalism

Studies addressing the links between structural power and regionalism have placed primary stress on the effects of hegemony. Various scholars argue that international economic stability is a collective good, suboptimal amounts of which will be pro- vided without a stable hegemon.93 Discriminatory trade arrangements, in turn, may be outgrowths of the economic instability fostered by the lack or decline of such a country.94 Offering one explanation for the trade-diverting character of PTAs during the interwar period, this argument is also invokedby many economists who maintain that the current wave of regionalism was triggered or accelerated by the U.S. deci- sion to pursue regional arrangements in the early 1980s, once its economic power waned and multilateral trade negotiations stalled.95 In fact, there is evidence that over the past ifty years the erosion of U.S. hegemony has stimulated a rise in the number of PTAs and states entering them.96 But why waning hegemony has been associated with the growth of regionalism since World War II, what effects PTAs formed in response to declining hegemony will have on the multilateral trading system, and whether variations in hegemony contributed to earlier episodes of regionalism are issues that remain unresolved.97

92. For example, Hurrell 1995, 68–71.

93. See Gilpin 1975; Kindleberger 1973; and Lake 1988.

94. See, for example, Gilpin 1975 and 1987; Kindleberger 1973; and Krasner 1976.

95. See,for example, Baldwin 1993; Bhagwati 1993; Bhagwati and Panagariya 1996; Krugman 1993; and Pomfret 1988.

96. Mansield 1998.

97. See,for example, McKeown 1991; Oye 1992; and Yarbrough and Yarbrough 1992.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

Some observers argue that as a hegemon’s power recedes, it has reason to behave in an increasingly predatory manner.98 To buffer the effects of such behavior, other states might form a series of preferential trading blocs, thereby setting off a wave of regionalism. Robert Gilpin suggests that this sort of process began to unfold during the 1980s, giving rise to a system of loose regional economic blocs that is coalescing around Western Europe, the United States, and Japan. He also points out that because of the inherent problems of ‘‘pluralist’’ leadership, these developments threaten the unity of the global trading order, a prospect that recalls Krugman’s claims about the adverse effects on global welfare stemming from systems composed of three trade blocs.99 The extent to which U.S. hegemonyhas actually declined and whether such a system is actually emerging, however, remain the subjects ofierce disagreement.

Furthermore, even if such a system is emerging, there are at least two reasons why the situation may be less dire than the preceding account would indicate. First, de- spite the potential problems of pluralist leadership, it is widely argued that global openness can be maintainedin the face of declining(or the absence of) hegemony if a small group of leading countries collaborates to support the trading system.100 The erosion of U.S. hegemony may have stimulated the creation and expansion of PTAs by a set of leading economic powers that felt these arrangements would assist them in managing the international economy.101 Drawing smaller states into preferential groupings with a relatively liberal cast toward third parties might reduce the capacity of these states to establish a series of more protectionist blocs and bind them to decisions about the system made by the leading powers. Especially if there is a multilateralframework (like the GATT/WTO) to which each leading power (includ- ing the declining hegemon) is committed and that can help to facilitate economic cooperation, the growth of regionalism during periods of hegemonic decline could contribute to the maintenance of an open trading system.

Second, Krugman argues that the dangers posed by a system of three trade blocs are muted if each bloc is composed of countries in close proximity that conduct a high volume of commerce prior to its establishment. Both he and Summers conclude that these ‘‘natural’’ trading blocs reduce the risk of trade diversion and that they make up a large portion of the existing PTAs.102 Regardless of this argument’s merits,

98. For example, Gilpin 1987, 88–90, and chap. 10.

99. See ibid.; and Krugman 1991a and 1993. On the problems associated with pluralist leadership, see also Kindleberger 1973.

100. See, for example, Keohane 1984; and Snidal 1985.

101. On this issue, see Yarbrough and Yarbrough 1992.

102. Krugman 1991a and 1993; and Summers 1991. Of course, these factors may be related, since an inverse relationship tends to exist between transportation costs and trade lows. However, some strands of this argument focus on high levels of trade, which may be a product of geographical proximity, whereas others focus on transportation costs, which are expected to be lower for states in the same region than for other states. See Bhagwati and Panagariya 1996, 7 fn. 7. Wonnacott and Lutz, who irst coined the term ‘‘natural trading partners,’’ argue that the economic development of states, the extent to which their economies are complementary, and the degree to which they compete in international markets also inlu- ence whether trading partners are natural. These factors, however, have received relatively little attention and we therefore do not examine them here. See Wonnacott and Lutz 1989.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

which have been hotly debated by economists,103 it begs an important set of ques- tions: Why do some ‘‘natural’’ trade partners form PTAs while others do not? And why do some ‘‘unnatural’’ partners do so as well? There is ample reason to expect that the answers to these questions hinge largely on domestic politicalfactors and the nature of political relations between states.

Central to the links between international political relations and the formation of PTAs are the effects of trade on states’ political-military power.104 Joanne Gowa points out that the efficiency gains from open trade promote the growth of national income, which can be used to enhance states’political-military capacity.105 Countries cannot ignore the security externalities stemming from commerce withoutjeopardiz- ing their political well-being. She maintains that countries can attend to these exter- nalities by trading more freely with their political-military allies than with other states. Since PTAs liberalize trade among members, Gowa’s argument suggests that such arrangements are especially likely to form among allies. In PTAs composed of allies, the gains from liberalizing trade among members bolster the alliance’s overall political-military capacity, and the common security aims of members attenuate the political risks that states beneiting less from the arrangement might otherwise face from those beneiting more.

Returning to the claims advanced by Krugman and Summers, certain blocs (for example, those in North America and Western Europe), therefore, may appear natu- ral partly because they are composed of allies, which tend to be located in close proximity and to trade heavily with each other.106 Furthermore, allies may be quite willing to form PTAs that divert trade from adversaries lying outside the arrange- ment, if they anticipate that doing so will impose greater economic damage on their foes than on themselves. In the same vein, adversaries have few political reasons to form a PTA, and allies that establish one are unlikely to permit their adversaries to join, thus limiting the scope for the expansion of preferential arrangements. Either situation could undermine the security of members, since some participants are likely to derive greater economic beneits than others even if all of them realize absolute gains in welfare. It is no coincidence, for instance, that preferential agreements be- tween the EC/EU and EFTA, on the one hand, and various states formerly in the Soviet orbit, on the other, were concluded only after the end of the Cold War and the

103. Bhagwati and Panagariya, for example, have lodged several criticisms against it. First, there are no clear empirical standards for gauging whether a given pair of trade partners is natural. Second, they challenge the assumption that high trade volumes among natural trade partners imply that low trade volumes exist among ‘‘unnatural’’ partners, thereby limiting the scope for trade diversion. Third, a high initial level of trade between states need not emanate from economic complementarities; instead, it might stem from preexisting patterns of discrimination. If so, these states may not be natural trade partners, and any PTA they establish may not be trade creating. See Bhagwati 1993, 34–35; and Bhagwati and Pana- gariya 1996.

104. On the relationship between trade and political power, see Baldwin 1985; Gowa 1994; Hirschman [1945] 1980; and Keohane and Nye 1977.

105. Gowa 1994.

106. On the relationship between alliances and proximity, see Farber and Gowa 1997, 411. On the relationship between alliances and trade, see Gowa 1994; and Mansield and Bronson 1997.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

collapse of the Warsaw Pact.107 Also, although deep political divisions continue to exist in various parts of the world, the lack of competing major power alliances may help to account for the relatively benign economic cast of the latest wave of regionalism.

Another way that regional arrangements can affect power relations is by inluenc- ing the economic dependence of members. If states that derive the greatest economic gains from a PTA are more vulnerable to disruptions of commercial relations within the arrangement than other participants, the politicalleverage of the latter is likely to grow. This point has not been lost on state leaders.

Prussia, for example, established the Zollverein largely to increase its political inluence over the weaker German states and to minimize Austrian inluence in the region.108 As a result, it repeatedly opposed Austria’s entry into the Zollverein. Simi- larly, both Great Britain and Prussia objected to the formation of a proposed customs union between France and Belgium during the 1840s on the grounds that it would promote French power and undermine Belgian independence. As Viner points out, ‘‘Palmerston took the positionthat every unionbetween two countries in commercial matters must necessarily tend to a community of action in the political ield also, but that when such community is establishedbetween a great power and a small one, the will of the stronger must prevail, and the real and practical independence of the smaller country will be lost.’’109 Furthermore, Albert O. Hirschman and others have described how various major powers used regional arrangements to bolster their political inluence during the interwar period and how certain arrangements that seemed likely to bear heavily on the European balance of power (like the proposed Austro-German customs union) were actively opposed.110

Since World War II, stronger states have continued to use PTAs as a means to consolidate their political inluence over weaker counterparts. The CMEA and the many arrangements that the EC established with former colonies of its members are cases in point. The Caribbean Basin Initiative launched by the United States in 1982 has been described in similar terms.111 A related issue is raised by Joseph M. Grieco, who argues that, over the past ifty years, the extent of institutionalization in regional arrangements has been inluenced by power relations among members.112 In areas where the local distribution of capabilities has shifted or states have expected such a shift to occur, weaker states have opposed establishing a formal regional institution, fearing that it would relect the interests of more powerful members and undermine their security. Another view, however, is that regional institutions foster stability and constrain the ability of members to exercise power. A recent study of the EU, for example, concludes that although Germany’s power has enabled it to shape Euro-

107. For a list of these arrangements, see World Trade Organization 1995, 85–87. 108. Viner 1950, 98.

109. Ibid., 87.

110. See, for example, Condliffe 1940; Hirschman [1945] 1980; Viner 1950, 87–91; and Eichengreen and Frankel 1995, 97.

111. For example, Pomfret 1988, 163.

112. Grieco 1997.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

pean institutions, Germany’s entanglement within these institutions has taken the hard edge offits interstate bargaining and eroded its hegemony in Europe.113

The links between power relations and PTAs remain important in the contempo- rary era, although they have not been studiedinsufficient depth. But in contrast to the interwar period, there is relatively little indication that regionalism has been the product of active attempts by states to promote their political-military power since WorldWar II. Barry Buzan attributes this change to the emergence of bipolarity, the decline of empires, and the advent of nuclear weapons.114 The latest wave of region- alism has been marked by especially few instances of states using PTAs to bolster their political-military capacity. That is probably one reason why regionalism has done less to divert trade over the past ifty years than during the interwar period.115 It also may help to explain why PTA membership has inhibited armed conlict through- out the post–World War II era.116 Gilpin has distinguished between benign and ma- levolent strains of regionalism. On the one hand, regionalism can promote interna- tional economic stability, multilateral liberalization, and peace. On the other hand, it can have a mercantilist tenor, degrading economic welfare and fostering interstate conlict.117 The available evidence suggests that, from an internationalpolitical stand- point, regionalism has been relatively benign since World War II, which may have dampened its potentiallypernicious economic consequences.118

Power and security relations have inluenced the formation and spread of PTAs. That such relations are also likely to affect the welfare implications of preferential arrangements poses a central challenge to the many economic studies that analyze regionalism in an international political vacuum. However, little contemporary re- search has directly addressed these topics. Moreover, the existing literature does not furnish an adequate understanding of how power and security relations have shaped regionalism over time; nor does it resolve questions about how recent changes in both regional and global politics have affected the rise and cast of the latest wave of PTAs.

MultilateralInstitutions, Strategic Interaction, and Regionalism

One of the most distinctive features of the two waves of regionalism occurring since WorldWar II is the multilateral framework in which they arose. Most contemporary PTAs have been established under the auspices of the GATT/WTO, which has at-

113. Katzenstein 1997b.

114. Buzan 1984.

115. For an empirical analysis of trade creation and trade diversion covering these periods, see Eichen- green and Frankel 1995.

116. See, for example, Nye 1971; and Mansield, Pevehouse, and Bearce forthcoming. 117. Gilpin 1975, 235.

118. At the same time, very little evidence has been accumulated on this score. Although a considerable amount of recent work has addressed the effects of trade lows on interstate conlict, far less attention has been paid to the inluence of institutions(both regional and multilateral) designed to guide trade. For some earlier research bearing on the relationship between regional economic arrangements and conlict, see Haas 1958; and Nye 1971. For an overview of the literature on the relationship between trade lows and conlict, see McMillan 1997.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

tempted to dampen trade diversion bylimiting members’ability to discriminate against third parties.119 But the GATT’s success in fostering trade-creating PTAs has been qualiied. Many arrangements formed by its economically less-developed members have been highlyprotectionist, and even the extent to which those preferential group- ings established among its developed members have been welfare enhancing is the subject of considerable dispute.

Furthermore, the absence of multilateral management has not always led to the formation of discriminatory regional arrangements. The liberal trading order of the nineteenth century was constructed on a bilateral and regional basis lacking any multilateral foundation. Also, Irwin points out that the economic and political dam- age caused by trade blocs formed in the 1930s might have been ameliorated if the League of Nations had not insisted on trying to promote the multilateral organization of commerce.120 In the same vein, Oye argues that regionalism ‘‘preserved zones of openness’’ early in that decade and that decentralized and ‘‘discriminatory bargain- ing was an important force for liberalization’’ during its middle and end.121

Article XXIV of the GATT outlines the conditions under which states are permit- ted to establish regionalintegration arrangements. Its stipulationthat PTAs eliminate internal trade barriers and its prohibition on increases in the average level of mem- bers’external tariffs do not preclude the possibility of trade diversion.122 But Eichen- green and Frankel note that the latter prohibition ‘‘explicitly rules out Krugman’s concern’’ about a beggar-thy-neighbor trade war arising in systems composed of a few large PTAs.123 To the extent that such a system has been emerging, the GATT/ WTO, therefore, may have an important role to play in averting what could otherwise be a destructive wave of regionalism.

Provisions for forming PTAs were made at the time of the GATT’s establishment because it was apparent that this body would be hard-pressed to forbid states from doing so. In addition, some decision makers seemed to believe that the provision in Article XXIV to completelyeliminate trade barriers within PTAs would complement GATT initiatives to promote multilateral openness.124 Indeed, parties to the GATT may have established PTAs at such a rapid rate during the past ifty years because they viewed regional liberalization as a stepping-stone to multilateral liberalization, a central premise of those who believe that preferential groupings will serve as build- ing blocks to global openness. Alternatively, GATT members may have formed such arrangements to help offset progressively deeper cuts in protection made at the mul- tilateral level and to protect uncompetitive sectors. A chief fear of those who view PTAs as stumbling blocks to multilateral liberalization is that arrangements formed for these reasons will divert trade and undermine future efforts at multilateralliberal- ization.

119. See Bhagwati 1991, chap. 5, and 1993; Eichengreen and Frankel 1995; and Finger 1993. 120. Irwin 1993.

121. Oye 1992, 9.

122. Bhagwati 1993, 35–36.

123. Eichengreen and Frankel 1995, 100.

124. See Bhagwati 1993; and Finger 1993.

https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899551002

P

Besides attempting to regulate the formation of PTAs, the GATT has made efforts to manage strategic interdependence among them. Preferential arrangements have formed in reaction to one another throughout each wave of regionalism. During the nineteenth century, this tendency was prompted by states’ desire to obtain access to MFN treatment. Doing so required them to enter the network of bilateral commercial arrangements undergirdingthe trading system, which generatedincreases in the num- ber of these arrangements and countries that were party to one.125 Throughout the interwar period, PTAs formed in reaction to each other due largely to mercantilist policies and politicalrivalries among the major powers.126

Strategic interactionhas continued to guide the development of PTAs since World War II.127 It has been argued, for example, that EFTA was created in response to the EEC; the latter also spurred various groups of LCDs to form regional arrange- ments.128 Furthermore, NAFTA has stimulated the establishment of bilateral eco- nomic arrangements in the Western Hemisphere and in the Asia-Pacii c region as well as agreements to conclude others.129 Yet contemporary PTAs have formed in reaction to each other for different reasons than before: GATT members have not established them to obtain MFN treatment, and they are not the products of mercan- tilist policies.