The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society思维导图

U347188394

2023-10-07

Annual

Contract

Companies

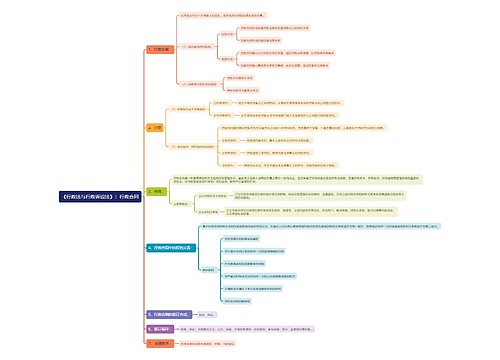

艺术管理、法律与社会杂志介绍

树图思维导图提供《The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society》在线思维导图免费制作,点击“编辑”按钮,可对《The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society》进行在线思维导图编辑,本思维导图属于思维导图模板主题,文件编号是:93ab5cdb099eb001981ebbaf3cbcf2a3

思维导图大纲

相关思维导图模版

The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society思维导图模板大纲

ISSN: 1063-2921 (Print) 1930-7799 (Online)Journal homepage:

https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjam20strong,https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjam20

How “Small” Are Small Arts Organizations?

Woong Jo Chang

To cite this article:

o

Organizations?, The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 40:3, 217-234, DOI:

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/showCitFormats?doi=10.1080/10632921.2010.50460410.1080/10632921.2010.504604

To link to this article:

https://doi.org/10.1080/10632921.2010.504604https://doi.org/10.1080/10632921.2010.504604

山 Article views: 484

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjam20https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjam20

LAW, AND SOCIETY, 40: 217–234, 2010

Copyright 装C Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 1063-2921 print / 1930-7799 online

DOI: 10.1080/10632921.2010.504604

How “Small” Are Small Arts

Organizations?

Woong Jo Chang

The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio

Small arts organizations (SAO) have not been studied in the field of cultural pol- icy and arts administration despite their purported importance. Through a review of the literature and extensive personal communications with professionals in the arts world, various meanings and manifestations of “smallness” across the creative sector are explored, highlighting the significant role of SAOs and their dynamic ecology. Multiple indicators of “smallness” are identified, whose possible combina- tions can enhance our ability to recognize both the uniqueness and sub-categories of organizations that currently are grouped into a single category of “small” arts organizations.

KEYWORDS creative sector, ecology, small arts organization, size

INTRODUCTION

Small arts organizations (SAO) are said to be the grassroots of the arts world and creative industries, providing a significant element of cultural diversity in local communities. The work of SAOs often inhabits areas that larger organizations fail (or hesitate) to reach. Despite their purported importance, SAOs have not been seriously studied. This article highlights the significant role of SAOs in the arts world and examines their dynamic ecology. To that end, through extensive personal communications with research managers, directors, and other administrators in arts agencies and national arts service associations, the article explores the various meanings and manifestations of “smallness” across the creative sector.

Address correspondence to Woong Jo Chang at chang.612@osu.edu.

218 CHANG

SIZE DOES MATTER

In the general practice and literatures of arts policy and administration, the size of arts organizations has seldom been seriously considered or studied. For instance, as the director of Research & Analysis at the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) pointed out, the NEA “does not segregate arts organizations by size during the grants review process.” 1 However, information and discussion about the size of arts organizations are important because the situations that SAOs face are different from those of larger arts organizations.

In 2009,at the 10th International Conference on Arts and Cultural Management, Ruth Rentschler and Jennifer Radbourne presented a paper titled “Size Does Matter: The Impact of Size on Governance in Arts Organizations” (2009). In the paper, the authors concluded that the size of arts organizations is a critical factor for conformance and performance of governance in arts organizations. They used mixed methods of survey and case studies on arts organizations in Victoria, Australia. Although this paper is limited to the board governance in arts organizations in Victoria, it does conclude that the governance of large and small arts organizations differs as their issues and needs are different.

The findings of Rentschler and Radbourne (2009) confirm the views that many research managers, directors, and other administrators in various arts agencies and national arts associations expressed to me in their personal communications (2008–2009) via e-mail and telephone. To mention one example, the League of American Orchestras (LAO) categorizes its member orchestras into as many as eight groups based on their annual budget size. As the director of Knowledge Center at LAO pointed out, the issues and challenges surrounding a small arts organization are very different from those of larger arts organizations.2

In fact, the small size of SAOs can be both a weakness and a strength. From one perspective, smaller budgets and lower levels of earned income constrain their per- formances. Conversely, SAOs’ smaller constituencies encompassing board mem- bers and audiences can allow them to experiment with new, innovative, and some- times controversial works. Therefore, the size consideration for arts organizations on one hand enables the development of more efficient and feasible management strategies for SAOs and, on the other hand, it enables various arts advocates, including arts agencies, to develop more implementable and effective support programs.

SMALL ARTS ORGANIZATIONS ARE TOO IMPORTANT TO BE NEGLECTED

One way to recognize the importance of SAOs is to consider their numbers. The number of SAOs can be determined partly from the Creative Industries Report

HOW “SMALL” ARE SMALL ARTS ORGANIZATIONS?

219

TABLE 1

Number of Arts Businesses with up to Five Employees in the

Columbus Metropolitan Area (Americans for the Arts 2006)

Employees

# of Arts Businesses

Percentage

0

51

3.40%

Less than 1

726

48.46%

Less than 2

1019

68.02%

Less than 3

1129

75.36%

Less than 4

1193

79.63%

Less than 5

1284

83.63%

All firms

1498

100%

by Americans for the Arts (AFTA). The report is formulated by documenting the data for both the nonprofit and for-profitarts sectors from the Dun & Bradstreet Business and Employment, from which we can derive localized data. Tables 1 and 2 indicate the number of SAOs determined after sorting the data by employee numbers. The tables show the cumulative numbers of arts businesses with up to five employees in the Columbus metropolitan area and in the state of Ohio, respectively.

The number of employees at SAOs has not been agreed upon yet. However, as can be seen in Tables 1 and 2, even arts businesses with one or no employees (perhaps relying mostly on volunteers) comprise approximately half of the arts organizations in both the Columbus metropolitan area and in the state of Ohio. If we borrow the concept of “microenterprise” from the business sector, which literally refers to an extremely small enterprise and is defined as a small business with five or fewer employees, requiring less than s35,000 as seed capital (Jones 2004, 5), then SAOs, as arts organizations with five or fewer employees, comprise 83.6% of arts businesses in Columbus and 86% in Ohio.

In terms of their numbers, the vividly visible significance of SAOs in the creative sector can be reconfirmed by the Statistics of U.S. Businesses from the

TABLE 2

Number of Arts Businesses with Up to Five Employees in the State of

Ohio (Americans for the Arts 2006)

Employees

# of Arts Businesses

Percentage

0

696

3.52%

Less than 1

10022

50.71%

Less than 3

15518

78.53%

Less than 4

16327

82.62%

Less than 5

16995

86.01%

All firms

19760

100%

220 CHANG

2006 U.S. census. In the arts-related sector (of NAICS 71—Arts, entertainment, & recreation, including both nonprofit and for-profit), the portion that SAOs (with 0 to 4 employees) occupy in terms of firm numbers makes up 61.34% (70,574 out of 115,049 firms) of all arts-related industries (U.S. Census Bureau, 2006a). The percentage increases in the performing arts and the related industry sector. SAOs comprise more than 78.44% (32,754 out of 41,755 firms) of all the performing arts, spectator sports, and related industries in terms of firm numbers (U.S. Census Bureau, 2006b). Although these statistics reflect industries that can be hardly included in the so-called “arts industry,” such as spectator sports and recreational industries, we can easily assume that if we can sort out the data of SAOs in the arts industry only, the percentage will not change that much (or may even be higher) because the sports and recreational industries are usually perceived to have larger organizations than the arts.

There are more possibilities for the higher numbers of SAOs when we consider that the public agency statistics do not provide an accurate number of SAOs because a considerable number of SAOs have not been incorporated.3

As Americans for the Arts also noted in their Creative Industries Report, their data underrepresents the nonprofit arts organizations because they rely on the database from Dun & Bradstreet. AFTA also admits that many individual artists are not included because many are not employed by a business (Americans for the Arts 2009). In addition, many administrators and artists participate in multiple SAOs, complicating the count of the actual number. It is quite possible that an artist or a musician can work in a large arts organization and also manage his/her own SAO. As the Ohio Arts Council (OAC 2001a) discovered, “the people who manage small arts organizations are teachers, professors, artists, homemakers, bankers, social workers, scientists and retired professionals.” Due to the difficulties to measure and define them, SAOs have been neglected in the general arts policy and administration literatures.

Rare among the literature on SAOs, in 2001 the OAC conducted an extensive survey of arts organizations in the state of Ohio, making a special effort to include SAOs, recognizing that “information about small arts organizations is essential to the blueprint” of the arts world. The agency categorized SAOs as those with an annual budget of less than s25,000. It also developed an extensive directory of more than four hundred SAOs listed by geographic region and specific art discipline (Ohio Arts Council 2001c). According to OAC’s findings, many SAOs are driven by a single passionate and highly committed individual and most are nonprofit entities, although some are small for-profit businesses operating at a financial risk. The OAC also concluded that it is time consuming to build an audience, because initial interest in SAOs diminishes over time. Finally, the agency found that most SAOs promoted their events through word of mouth (Ohio Arts Council

HOW “SMALL” ARE SMALL ARTS ORGANIZATIONS? 221

DEFINITIONS: HOW “SMALL” IS SMALL?

Like OAC, many agencies and associations have tried to define SAOs. Although distinctions are made according to budget size, there is no generally agreed upon standard for defining SAOs across disciplines; sometimes there are even differ- ences within a specific discipline. In the following discussion, I will explore various operational definitions of smallness across different sectors (for-profit and nonprofit) and arts disciplines.

A discrepancy can be found in the definition of SAOs in terms of budget size (revenue or receipt size), especially between the for-profit sector’s view articulated by the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) and the nonprofit sector’s view used by state and local arts agencies. Significant variation is evident even within the nonprofit sector. Moreover, the differences exhibited among the national associations representing different arts disciplines are even more pronounced.

The For-Profit Sector

The legislation that founded the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) in 1953 provides an official definition of a small business. The Small Business Act of 1953 states that a small business is “one which is independently owned and operated and which is not dominant in its field of operation” (6). To allow for industry differences, the exact numerical standard for “small” was later determined administratively by Small Business Size Regulations (13 CFR §121). The SBA established a table of size standards using numerical indicators such as the number of employees and average annual receipts of a business concern. According to the Small Business Act of 1953, the SBA can adjust the small business size standards based on the recommendations proposed by other Federal agencies. These numerical standards vary across all industries from one to forty million dollars and from five to 700 employees. If an arts organization fits the SBA standard of a small business, it can qualify for many programs administered by the SBA, including the loan program.

The SBA regulates and defines small businesses in arts industries as those organizations that have less than seven million dollars for their annual receipts. The SBA’s standards focus on for-profit businesses and are not designed for nonprofit organizations. Therefore, the relatively large receipt standard of up to seven million dollars is likely to include entertainment and media businesses and other copyright- based industries where large corporations can operate larger budgets.

The Nonprofit Sector

Many public arts agencies, at the state or local levels, have recognized the signif- icance of SAOs and have tried to classify and define them for programmatic and

222 CHANG

eligibility purposes. Nevertheless, many still do not have a concrete definition of SAOs and feel they are “grasping in the dark when it comes to small arts organi- zations”.4 For example, the Greater Columbus Arts Council (GCAC) has offered a number of programs to support arts organizations in the Columbus metropolitan area regardless of size. SAOs have frequently taken advantage of these programs, often because they have few internal resources of their own and because these programs are mostly free of charge. Thus, GCAC serves SAOs even though the agency does not have a specific category for them.5

Although some arts agencies use budget size as a criterion for SAOs, this cri- terion varies considerably. According to the Director of Community Engagement and Strategic Initiatives at Fine Arts Fund (FAF) in Cincinnati, FAF does not have an explicit standard for SAOs, but considers arts organizations with annual budgetsunders100,000 as SAOs.6 Similarly, the Los Angeles County Arts Com- mission (2004, 1) also classifies arts organizations with annual budgets of less than s100,000 as SAOs. Alternatively, the Ohio Arts Council defines an SAO as (1) an organization with a budget of less than s30,000 (which was updated recently from s25,000)7 that is (2) a non-profit (or “non-profit” in intent) arts organization, and (3) not part of a university or college.

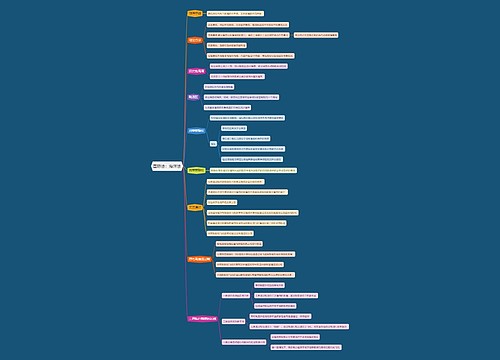

Figure 1 compares the official definitions of SAOs according to SBA, OAC, FAF, and LACAC. By comparison, we can see that different public agencies have different standards for identifying SAOs. Note that these public agencies rely on receipts, revenue, and budget to determine the financial size of an SAO. Strictly speaking, each of these measures is subtly different from one another. However,

FIGURE 1 Examples of official definitions of SAOs in terms of budget.

HOW “SMALL” ARE SMALL ARTS ORGANIZATIONS? 223

for our purposes, receipts, revenue, and budget are comparable enough to illustrate the discrepancy of size standards used in defining SAOs.

The issue regarding the official definitions of SAOs shown in Figure 1 is that these public agencies crudely bundle up the wide range of SAOs based only on a single standard, which does not reflect the variety of SAOs. This raises the need to explore definitions of SAOs across different disciplines.

SAOs DEFINED BY VARIOUS DISCIPLINES

National arts service associations have tried to define SAOs in their particular dis- ciplines. They have also tried to protect the interest of both the public and member organizations. Similar to the Small Business Administration, Ohio Arts Council, Los Angeles County Arts Commission, and Fine Arts Fund in Cincinnati, most national arts service associations also depend on a single variable (financial stand- ing) to define SAOs. This section reviews the cases of various national arts service associations. These include the Theatre Communications Group (TCG) and the American Association of Community Theatres (AACT) for theaters, the League of American Orchestras (LAO) for orchestras, DanceUSA for dance companies, Opera America for opera companies, and the American Association of Museums (AAM) for museums.

Theater

Historically, many concepts of small theaters have been introduced, such as “Little Theatre,” “Community Theatre,” and “Pro-am Theatre.” Rather than as ad- ministrative strategies that deal with issues and challenges of small theaters, these concepts were developed as part of experimental and civic theater movements. For more administrative issues, Theatre Communications Group can be a good source. TCG represents approximately 500 nonprofit theater organizations that range in size from budgets of s50,000 to more than s40 million. As the response to the member theater’s specific needs, TCG categorizes them into six budget groups as listed in Table 3.

As can be seen in Table 3, TCG identifies its member theaters with Group 1 representing theaters with the smallest budgets and Group 6 representing those with the largest budgets.

224 CHANG

TABLE 3

Theatre Company Size Groupings by TCG

Group

Budget Size

Number of Theatres

Group 1

s50,000–s499,999

19

Group 2

s500,000–s999,999

35

Group 3

s1,000,000–s2,999,999

54

Group 4

s3,000,000–s4,999,999

28

Group 5

s5,000,000–s9,999,999

31

Group 6

s10,000,000 and above

29

the Web site of TCG, minimum operating expenses for members should be at least s50,000 in the most recently completed fiscal year. For a partial reason, the Management Programs Research Associate at TCG told me that there are many regional memberships which include small theatres with budgets less than s50,000.8

The American Association of Community Theatres includes many smaller theaters that TCG does not include. According to the AACT website, AACT categorizes its members into seven groups based on the annual budget as listed in Table 4.9

ACCT considers theaters with an annual budget under s100,000 to be small. However, although the association categorizes theater size by the theater’s annual budget as seen in its Membership Categories, there are other considerations such as how many shows the theater produces per year or how many volunteers the theater has. For example, a theater with many volunteers can produce as much as one with a larger budget. Therefore,AACT considers a theater that produces three shows or less per year as being “really small” .10

Orchestra

Like TCG and AACT, the League of American Orchestras categorizes its member orchestras using budget size. LAO encompasses nearly 1,000-member

TABLE 4

Community Theater Size Groupings by AACT

Annual Budget

Number of Theaters

1

under s10,000

223

2

s10,000–s24,999

138

3

s25,000–s99,999

292

4

s100,000–s249,999

155

5

s250,000–s499,999

68

6

s500,000–s999,999

33

7

s1,000,000 and over

18

HOW “SMALL” ARE SMALL ARTS ORGANIZATIONS?

225

TABLE 5

Orchestra Size Groupings by League of American Orchestras

Group

Budget Size

Number of Orchestras

Group 1

s14,400,000 and greater

25

Group 2

s6,000,000–s14,399,000

29

Group 3

s2,800,000–s5,999,000

31

Group 4

s1,820,000–s2,799,000

35

Group 5

s1,000,000–s1,819,000

63

Group 6

s500,000–s999,000

113

Group 7

s150,000–s499,000

223

Group 8

Less than s149,000

657

symphony and chamber, youth, and collegiate orchestras of all sizes. It categorizes its member orchestras based on their annual budget, which determines League Meeting Groups so that orchestras may meet with their peer orchestras and share similar issues. In the fiscal year of 2006–2007, LAO categorized its member organizations into eight groups as can be seen in Table 5.11

Among the groups, LAO usually includes Groups 7 and 8 in the smaller budget orchestra category, which is still relative. LAO’s director of Knowledge Center explained to me that the meeting groups are more of an internal league catego- rization.12 It is a way for them to group peer orchestras with each other for more specific issues and challenges. According to Wilson, smaller orchestras are differ- ent from medium and large-sized orchestras mainly in terms of resources that are available to them.

Although not a specific discipline as TCG or LAO, North American Perform- ing Arts Managers and Agents (NAPAMA) also lay out a category to group their members as organizations with annual contract fees under s250,000, s250 001–s750,000 and over s750,000, as can be seen in Table 6 (NAPAMA Website).

NAPAMA does not show specific interest in small organizations; however, it is interesting to note that it charges individual members and self-managed artists a membership fee of s150, which is the same as that for organizations with an annual contract fee under s250,000. That is, NAPAMA treats organizations with annual contract fees under s250,000 equally as individual members.

TABLE 6

NAPAMA’s Membership Dues by Annual Contract Fee

Annual

Contract Fee

Membership Dues

Under s250,000

s 150

s250 001–s750,000

s300

Over s750,000

s400

226 CHANG

TABLE 7

Opera Company Size Groupings by Opera America

Level

Budget Size

No. of Companies

Level 1

s10,000,000 and above

12

Level 2

s3,000,000–s9,999,999

17

Level 3

s1,000,000–s2,999,999

14

Level 4

Under s1,000,000

13

Opera

Opera America also categorizes its member opera companies by budget size. We can find the most recent attendance figures, operating budgets, trends in giving and public funding, and numbers of performances and productions in Opera America’s

Dance

DanceUSA also categorizes dance companies by budget size. As can be seen in the membership page on the Website of DanceUSA, members are categorized into eight groups based on the operating revenue, which is seen in Table 8. According to Kellee Edusei, the membership manager at DanceUSA, this categorization is more of practical use to manage the association’s membership.13

John Munger, the Director of Research and Information at DanceUSA, tried to qualify the dance companies in the U.S. into small, medium, and large sizes. In his article, “Dancing with dollars in the millennium” (2001), he set different budget

TABLE 8

Dance Company Size Groupings by DanceUSA

Level

Operating Revenue Size

1

Up to s100,000

2

s100,001∼s200,000

3

s200,001∼s400,000

4

s400,001∼s600,000

5

s600,000∼s999,999

6

s1,000,000∼s2,999,999

7

s3,000,000∼s7,999,999

8

s8,000,000 or more

HOW “SMALL” ARE SMALL ARTS ORGANIZATIONS?

227

TABLE 9

Ballet Company Size Groupings (Munger 2001)

Company Size

Budget Size

Large

s5,000,000 and greater

Medium

s1,000,000∼s5,000,000

Small

Less than s1,000,000

categorizations for ballet companies and modern dance companies. As can be seen in Table 9, large ballet companies have budgets in excess of s5 million and medium ballet companies have budgets between s1 million and s5 million. According to Munger, small ballets have budgetsunders1 million and generally take two forms, which can be classified as “semiprofessional” and “chamber ballets.” These have small casts of six to ten dancers and only two or three administrators.14

As for modern dance companies, Munger identifies large companies to have budgets in excess of s860,000 and medium companies to have budgets between s250,000 and s860,000, which automatically sets small companies to have budgets under s250,000. However, they do not have comprehensive data to address most small modern dance companies.15 Table 10 shows Munger’s (2001) size groupings for modern dance companies.

According to Munger’s identifications, ballet dance companies in Levels 1 to 5 and modern dance companies in Levels 1, 2, and part of Level 3 would be considered small dance companies in DanceUSA. Munger shared his updated categorization of dance organizations in America using the following variables to categorize dance companies: (1) operating expense budget, (2) genre (e.g., ballet, modern/contemporary, tap, culturally specific, jazz, etc.), (3) number of dancers, (4) number of staff, (5) impact of individual donations, (6) impact of touring, (7) whether dancers are salaried employees or freelance contractors, and (8) founding date (duration of company).16 Using these variables, Munger examined various dance companies and “sorted them into the near vicinity of category-separations that were used in the past. [My] experience has taught [me] for nearly two decades that it has been most useful in general to categorize dance companies by a combination of genre and expense budget.” 17 Table 11 shows the most updated (as of May 2009) categories of American dance companies formulated by Munger.

TABLE 10

Modern Dance Company Size Groupings (Munger 2001)

Company Size

Budget Size

Large

s860,000 and greater

Medium

s250,000∼s860,000

Small

Less than s250,000

228

TABLE 11

Updated Dance Company Size Groupings18 (Munger 2009)

Company Size

Budget Size

Genre

Notes by Munger (2009)

Very Large Companies

∼ s15,000,000

Any Genre

There are only about seven or eight and they are all ballet except for Alvin Ailey.

Large Ballet

s14,9000,000 ∼ s6,000,000

Ballet

The s6 million lower limit is now in question because of the large number of companies reducing their budgets as a result of the financial catastrophes of the 2000s.

Large Modern

s6,000,000 ∼ s1,500,000

Modern

Large Modern is “smaller” than “Large Ballet” and the same as “Medium Ballet” in budget size.

Medium Ballet

s6,000,000 ∼ s1,500,000

Ballet

Small Ballet

s1,500,000 ∼

Ballet

Medium Modern

s1,500,000 ∼ s500,000

Modern

Small Modern

s500,000 ∼

Modern

Large Culturally Specific

∼ s500,000

Culturally Specific

Only a handful of the approximately 80 dance companies in the U.S. with budgets over s1 million are genres other than ballet or modern.

Medium Culturally Specific

s499,000 ∼ s100,000

Culturally Specific

Very Small Companies

s100,000 ∼

Any Genre

HOW “SMALL” ARE SMALL ARTS ORGANIZATIONS? 229

Munger admitted that “many exceptions occur in the process of categorization and [I make] a judgment call based on general trends in that case. For example, ‘small ballet’ category is now under review.” Munger gave two reasons for this. One is that “so-called ‘Chamber Ballet’ companies have blossomed and are differ- ent from ‘traditional hierarchical’ ballet companies of the same budget size.” The other reason is that “there is an emerging category—or potential category—that is typically a school rather than a company, but that has serious performance capa- bility using the most advanced students.” 19 However, while Mungeris developing other variables by which to categorize SAOs, DanceUSA continues to base its cat- egorization of American dance companies based mainly on budget size and genre.

Museum

When it comes to museums, there is unfortunately no absolute measure of “large” and “small,” not even if we focus on budget size (as opposed to physical size, number of visitors, collection size, or any other potential measure of size). For example, the American Association of Museums’ (AAM) Museum Assessment Program uses s125,000 as its smallest budget category. The Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), a federal agency, uses s250,000 as its smallest bud- get category. AAM’s Small Museum Administrators Committee defines “small” as museums with budgets of s350,000 or less. The

Philip Katz, Assistant Director for Research at AAM, discussed the recent efforts of the American Association for State and Local History (AASLH) to define small museums. AASLH has a Small Museum Committee, which has been trying to establish a definition of “small” on which AASLH, AAM, and IMLS could all agree. To that end, the committee conducted a survey in 2007 and found that budget size is the main characteristic, with 80% of the 455 respondents agreeing that the defining budget is s250,000 or less. According to Katz, there was also considerable agreement about the other characteristics of a small museum: “Zero to three paid staff, dependence on volunteers, physical size of the museum, collections size and scope”.20 The AASLH Committee created a working definition that seems to have gained general agreement: “A small museum’s characteristics vary, but they typically have an annual budget of less than s250,000,operate with a small staff with multiple responsibilities, and employ volunteers to perform key staff functions. Other characteristics such as the physical size of the museum, collections size and scope, etc. may further classify a museum as small.”21

230 CHANG

CROSS-DISCIPLINE COMPARISON OF SIZE

AND “SMALLNESS”

Many professionals in national arts service associations recognize that the issues and challenges surrounding arts organizations vary depending on the size of the organization. It appears that national arts service associations are also trying to maintain the even distribution of their member organizations in each category in order to manage their members more effectively. As Munger pointed out, in the case of DanceUSA, the categories shown in the various national arts associations are “rather a political convenience within the membership.”22

As I have illustrated above, different disciplines use different financial standards by which to define SAOs. This is shown in Figure 2. Furthermore, a comparison of Figures 1 and 2 shows us that the SAO standards of various national arts associations for budget size (from under s250,000 to under s1 million) allow a relatively larger budget than those of public arts agencies (from under s25,000 to under s100,000), yet they allow a much smaller budget than that of the U.S. Small Business Administration (under s7 million).

Perhaps it may not be that useful to explore the standards for SAOs across different sectors and disciplines because it is becoming more difficult to place many emerging SAOs in traditional sectors and arts disciplines. Due to SAOs’ flexible and experimental nature, it is not easy to tell which emerging SAO belongs to which discipline. In fact, there is an increasing number of new multidisciplinary SAOs. Furthermore, a considerable number of SAOs belong not only to the nonprofit sector, but also the for-profit sector. As mentioned in the characteristics of SAOs along with OAC’s findings, some SAOs do not even realize that they are not

FIGURE 2 Small arts organizations defined by various disciplines.

HOW “SMALL” ARE SMALL ARTS ORGANIZATIONS? 231

nonprofit organizations, but are for-profit businesses that are operating at a deficit. However, as the American Association for State and Local History recognized with regard to museums, a working definitionis necessary in order to better respond to the needs of SAOs.

RECOGNIZING THE DIVERSITY OF SMALL ARTS ORGANIZATIONS

Using traditional standards that rely on a single variable to define small arts organizations makes it difficult to grasp the ecology of SAOs in the creative sector, that is, their dynamic interrelation with other organizations and individuals in and outside of several different sectors and disciplines. In fact, relying on budget size as the only variable may be misleading. Using different variables will lead to different conclusions regarding whether an SAO is small. Considering other variables and concepts would not only be useful, but is also necessary and would strengthen our understanding of SAOs.

Multiple indicators, such as human resources and community impact, as well as financial resources (e.g., receipts, revenue, budget) could be developed to define SAOs. Using the variable of number of employees (human resources) would yield a different breakdown between small arts organizations versus larger arts organizations. For example, an arts organization may be categorized as mid-size because its annual budget is more than s100,000. However, this same organization may have zero employees because it is operated by volunteers. Thus, each indicator produces a different classification of size for the same organization.

Using the variable of the impact on community would result in categorizing some SAOs with small budgets as “large” in terms of community impact. This impact might be measured in various ways. One might measure the number of people involved (including paid staff, volunteers, and audiences) and the hours that the people commit to the organization. It is quite possible that some arts organizations are so small by budget size that they only appear online yet reach many members of the community, perhaps more so than some traditional arts organizations with larger budgets. In this case, if categorized by their impact on the community, such organizations would be considered “large.” Likewise, the physical size of the organization’s facility can also be used as a variable to determine whether the SAO is regarded as “small” or “large.” For instance, John Munger’s updated categorization of dance organizations in America uses multiple variables, such as number of artists and staff, genre, and impact of different organizational activities, in addition to budget size. Similarly, the Small Museum Committee of the AASLH, which incorporated multiple variables by which to establish an integrated definition of “small,” provides a useful model for identifying SAOs, as well.

232 CHANG

In addition, my examination of SAOs and the various standards used to define them led me to discover yet more ways of recognizing subtle but important differences among SAOs and their significance. As I tried to evaluate SAOs along the number of multiple indicators identified above for SAOs, I realized that they can also be subdivided along the lines of their intention for future growth, forms of collaboration in which they engage, and their degree of community involvement.

For instance, it might be possible to categorize SAOs by their future aspiration to grow and be more professional (not just bigger) under the label of “Emerging.” Such SAOs have much possibility to grow to be larger arts organizations. Alterna- tively, we might categorize them as “Entrepreneurial,” in the sense that they aim to both grow in terms of budget, personnel, and/or audience, or even in terms of increasing professionalism.

Next, considering SAOs along their form of collaboration, many SAOs might be called either “Self-Subsidizing” or “Cooperatives.” The former includes SAOs whose members collaborate to subsidize a kind of work in which they are col- lectively interested, while the latter shares resources that are mainly used to sup- port the work of individual member artists. Unlike the Emerging type, the Self- Subsidizing type is generally satisfied with its size. In actuality, the possibility of SAOs of this type to grow to be larger arts organizations may be limited due to their nature of being a volunteer-based organization. The Cooperative type of SAOs, in terms of their intention to grow, are more interested in developing and expanding the careers and work products of individual member artists by pro- viding and sharing resources, facilities, and equipments, than in expanding their audiences (as Emerging SAOs aspire to do).

Finally, if we were to examine SAOs by their degree of involvement in the local community, we could identify civic arts organizations that rely heavily on support from the local community in terms of both money and volunteer participation under the label of the “Civic Type.” Since their target audiences are usually more focused in the local community, this type of SAOs usually includes the name of the community in the organization’s name.

To sum up, both a review of the literature and extensive communications with research managers, directors, and other administrators in arts agencies and national arts service associations suggest the following set of multiple indicators of “smallness”: (1) intention for future growth, (2) the form of collaboration in which SAOs engage, (3) the degree of community involvement, as well as (4) the number of paid staff, (5) volunteers operating key functions, (6) facility size, (7) annual budget, and (8) the size and scope of the collections and/or seasons. The possible combinations of these indicators enhance our ability to recognize both the uniqueness and the subcategories of organizations that currently are all grouped into a single category of “small” arts organizations. Using multiple variables for determining the different variants of SAOs is likely to yield a more appropriate and precise identification of SAOs and a better understanding of their issues and

HOW “SMALL” ARE SMALL ARTS ORGANIZATIONS? 233

needs. Indeed, this would be a worthwhile effort and a well-grounded starting point for acknowledging the importance of SAOs in the creative sector and in our local communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author wishes to thank his professors in the Arts Policy and Administration Program at the Ohio State University, Dr. Margaret Wyszomirski and Dr. Wayne Lawson, for their expert advice and feedback throughout the research and writing of this paper. He is also grateful to the many people who shared their time, knowledge, and experiences with him in the process of exploring this subject.

Notes

1. Sunil Iyengar, e-mail message to author, February 20, 2009.

2. Jan Wilson, e-mail message to author, December 2, 2008.

3. Dan Katona, personal communication with author, May 8, 2009.

4. Ruby Classen, personal communication with author, May 8, 2009.

5. Robin Pfeil, e-mail message to author, March 19, 2009; Ruby Classen, personal commu- nication with author, May 8, 2009.

6. Vanessa White, telephone communication with author, February 17, 2009.

7. Dan Katona, personal communication with author, May 8, 2009.

8. Ilana Rose, e-mail message to author, December 5, 2008.

9. Julie Crawford, telephone communication with author, 22, 2009.

10. Julie Crawford, e-mail message to author, May 22, 2009.

11. Julie Crawford, e-mail message to author, May 22, 2009.

12. Jan Wilson, e-mail message to author, December 2, 2008.

13. Kellee Edusei, telephone communication with author, May 22, 2009. 14. John Munger, e-mail message to author, May 29, 2009.

15. John Munger, e-mail message to author, May 29, 2009.

16. John Munger, e-mail message to author, May 29, 2009.

17. John Munger, e-mail message to author, May 29, 2009.

18. John Munger, e-mail message to author, May 29, 2009.

19. John Munger, e-mail message to author, May 29, 2009.

20. Philip Katz, e-mail message to author, December 3, 2008.

21. Philip Katz, e-mail message to author, December 3, 2008.

22. John Munger, e-mail message to author, May 29, 2009.

REFERENCES

American Association for State and Local History. 2007. What is the definition of a small museum? Survey results.

American Association of Community Theatre. 2010. AACT Membership Options. http://www.aact2. org/?page=membershipoptions

234 CHANG

American Association of Museum. 2000.

Americans for the Arts. 2008a.

—— . 2008b.

DanceUSA. 2010. Dance companies membership categories and benefits.

Jones, S. R. 2004.

Munger,J. R. 2001.

National Archives and Records Administration’s Office of the Federal Register (OFR) and the Government Printing Office (GPO). 1996/2009. Small Business Size Regulations. 13 C.F.R. § 12.

op3=and;rgn3=Section;view=text;idno=13;node=13:1.0.1.1.16;rgn=div5

Ohio Arts Council (OAC). 2001a. Small arts organizations: Key elements of the infrastructure. http: //www.ohiosoar.org/SmallArts/infrastructure.asp (accessed October 20, 2009).

—— . 2001b. Small arts organizations methodology.

—— . 2001c. Small arts organizations relationship to the blueprint.

Opera America. 2008.

Rentschler, R., and Radbourne,J. 2009. Size does matter: The impact of size on governance in arts or- ganizations. Paper presented at the 10th International Conference on Arts and Cultural Management, Dallas, Texas.

Theatre Communication Group. (2008).

U.S. Census Bureau. 2006a. Statistics of U.S. businesses: 2006: NAICS 71—Arts, entertainment, & recreation.

-—– . 2006b. Statistics of U.S. businesses: 2006: NAICS 711—Performing arts, spectator sports, & related industries.

U.S. Small Business Administration. (n.d.). Firm size data.

查看更多

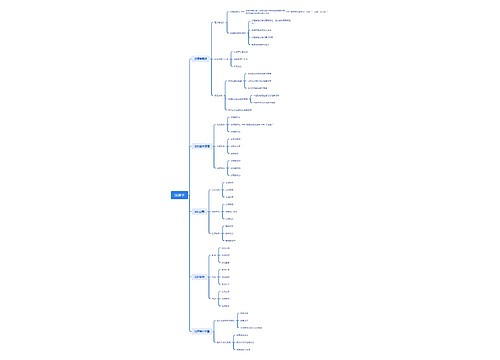

Contract workflow management 思维导图

U873425174

U873425174树图思维导图提供《Contract workflow management 》在线思维导图免费制作,点击“编辑”按钮,可对《Contract workflow management 》进行在线思维导图编辑,本思维导图属于思维导图模板主题,文件编号是:5bdf9d6bfb865f378ed9a302b06e2ccc

ARTS思维导图

U349206095

U349206095树图思维导图提供《ARTS》在线思维导图免费制作,点击“编辑”按钮,可对《ARTS》进行在线思维导图编辑,本思维导图属于思维导图模板主题,文件编号是:f60dfcd30c9d3eab3714823e77803fec

相似思维导图模版

首页

我的文件

我的团队

个人中心