PRAGMATICS思维导图

U782058360

2024-11-06

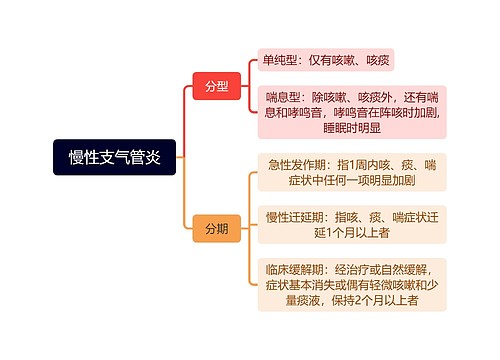

a.你能帮我把它捡起来吗?

第四组:关于听者做某事的愿望或意愿的句子

你应该偶尔给他们写信

语用学内容详述

树图思维导图提供《PRAGMATICS》在线思维导图免费制作,点击“编辑”按钮,可对《PRAGMATICS》进行在线思维导图编辑,本思维导图属于思维导图模板主题,文件编号是:5c88b9d082a71ef59715fa269758e09b

思维导图大纲

相关思维导图模版

PRAGMATICS思维导图模板大纲

Introduction

After grammatical and semantic analysis of a sentence, there still seems to be something unsaid about it. For instance, we Chinese often say to each other when we meet “Have you eaten yet?” After some analysis, we feel that it does not mean the speaker is interested in the hearer’s state of stomach and the former is not ready to treat the latter to a big meal if he has not eaten. In short, it serves, more often than not, as a kind of greeting, or just saying something for its own sake. There are many other instances in which the literal meaning of the utterance is far away from the intended meaning of the speaker and that the hearer can almost always work out what the speaker intends to convey. So the natural realization is that grammatical analysis alone is not enough, and that when language is used, it behaves quite differently from when it is studied as an abstract system. It seems the case that once language is used, some extra meaning is produced beyond and under the literal meaning. This realization gradually gives birth to

What is the difference between grammatical analysis and pragmatic analysis? First, grammatical studies look for rules while pragmatic studies look for principles. Rules are black and white, i.e. you are either right or wrong. For instance, you have to say “He studies linguistics”; the

Pragmatics, as the study of language in use, is a young science. G. Leech (1983) remarks that “fifteen years ago, pragmatics was mentioned by linguists rarely, if at all.” And if indeed pragmatics was mentioned at all, it was more in the guise of “ragbag” or, as someone once put it, a “waste-paper basket” designed to take care of the overflow from semantics, in the same way that semantic itself once had been assigned the task of explaining whatever syntactic theories had been proved unable to deal with. Prejudice against pragmatics has not prevented it from developing. Since the early 1970s, a growing interest in pragmatics and pragmatic problems has been witnessed worldwide. The international

In many ways, pragmatics is the study of speakers intended meaning, or even the “invisible” meaning, that is, how hearers recognize what is meaning even when it isn’t actually said or written. Take a newspaper advertisement for example, think not only about what the words might mean, but also about what the advertiser intended them to mean:

BABY & TODDLER SALE

In the normal context, we assume that this store has not gone into the business of selling babies over the counter, but rather that it is advertising clothes for them. The word

relating to the sale of baby clothes and not of babies. This example tells us that when we hear or read pieces of languages, we normally try to understand not only what the words mean, but also what the speaker or writer intended to convey. Thus, pragmatics can also be defined as the study of speaker meaning.

Micropragmatics

We have no difficulty understanding this utterance: “I was waiting for the bus, but he just drove by without stopping”, though this

Now a lot of research has been done on the larger chunks of language, a whole conversation, an article or even a chapter of a novel or one act of a play. In such cases the interest is focused on language user interaction. These studies look deep into the mechanisms by which speakers/writers encode their message in skillful ways and how hearers/readers arrive at the intended meanings in spite of the differences between the literal meaning and the intended meaning. This approach of study is called macropragmatics.

In this section, we only focus on micropragmatics. Macropragmatics will be discussed in the rest of the chapter.

Reference

In semantics, it is often assumed that the words we use to identify things are in some direct relationship to those things. However, it is not as simple as that. For example:

a: Where is the fresh salad sitting? b: He’s sitting by the door.

a: Can I look at your Shakespeare? b: Sure, it’s on the shelf over there.

These examples make it clear that we can use names associated with things (salad) to refer to people and names of people (Shakespeare) to refer to things. The key process here is called inference. An inference is any additional information used by the hearer to connect what is said to what must be meant. In example (2), the hearer has to infer that the name of the writer of a book can be used to identify a book by that writer. In pragmatic, the act by which is speaker or writer uses language to enable a hearer or reader to identify something is called reference.

Deixis

In all languages there are many words and expressions whose refence depends entirely on the situational context of the utterance and can only be understood in light of these circumstances. This aspect of pragmatics is called deixis, which means “pointing” via language. Any linguistic form used to do this “pointing” is called a deictic expression. In English, for example, there are some words that cannot be interpreted at all unless the context, especially the physical context of the speaker, is known. These are words like

You’ll have to bring that back tomorrow, because they aren’t here now.

Out of context, we cannot understand this sentence because it contains a number of expressions such as

There are five types of deixis.

Person deixis: Any expression used to point to a person is an example of person deixis, for example,

Time deixis: Words used to point to a time are examples of time deixis, for example,

Space/spatial/place deixis: Words used to point to a location are examples of space deixis, for example,

Discourse deixis: Any expression used to refer to earlier or forthcoming segments of the discourse is an example of discourse deixis, for example,

Social deixis: Honorifics (forms to show respect such as Professor Li) are often encountered in the languages of the world. They are often thought of as an aspect of person deixis, but although organized around the deictic centre like space and time deixis, honorifics involve a separate dimension of social deixis. Honorifics encode the speaker’s social relationship to another party, frequently but not always the addressee, on a dimension of rank. Of course, there are other aspects of social deixis, for example, some linguistic expressions may be used to encode specific kinship relations, e.g.

Anaphora

When we establish a referent and subsequently refer to the same object, we have a particular kind of referential relationship. For example:

a: Can I borrow your dictionary? b: Yeah, it’s on the table.

Here, the word

Mostly the relation between the antecedent and the anaphor is direct, but sometimes the connection between them is indirect. For example:

I walked into the room. The

The antecedent here is

Presupposition

If someone tells you “Your girlfriend is waiting outside for you”, thee is an obvious assumption that

you have a girlfriend. If you are asked the following question, there are at least two assumptions involved:

When did you stop beating your wife?

Here, the speaker assumes that you used to beat you wife, and that you no longer do so. Such assumptions by the speaker or writer are called presuppositions. Questions like this, with built-in presuppositions, are very useful devices for interrogators or trial lawyers. For example, if you are asked by your teacher:

How often do you cheat in your examinations?

There is a presupposition that you do, in fact, cheat in examinations. If you simply answer the

How do we know that something is built into a sentence as presupposition? One of the tests used to check for the presuppositions underlying sentences involves negating a sentence with a particular presupposition and considering whether the presupposition remains true. For example, if someone says:

I used to regret marrying her, but I don’t regret marrying her now.

The presupposition

This is called the constancy under negation test for presupposition.

In any language, there are some expressions or constructions which can act as the sources of presuppositions. This kind of expressions or constructions are called presupposition triggers. The following are some examples, where the presupposition triggers themselves are italicized, and the symbol “>>” stands for “presupposes”:

Definitive descriptions

John saw/didn’t see

There exists a man with two heads.

Factive verbs

John

John was in debt.

Change of state verbs

Joan

Joan hadn’t been beating her husband.

Iteratives

The flying saucer came/didn’t come

The flying saucer came before.

Temporal clauses

While

h

Chomsky was revolutionizing linguistics.

Cleft sentences

It was/wasn’t Henry that kissed Rosie.

Someone kissed Rosie.

Comparisons and contrasts

Carol is/isn’t a

Barbara is a linguist.

Macropragmatics

More often than not, we don’t confine our study to individual utterances, but extend our analysis of larger

pieces of language, for the simple reason that language use is an intricate process. In macropragmatics, there have been different theories. Philosophers, in their search for answers to their philosophical puzzles, turned to language studies. They came up with several approaches to how language is used and how certain problems seem to be explained by language in use. They often refer to these approaches as philosophy of language but linguists prefer to call it pragmatics. What follows is an introduction to some influential theories on language use.

Speech act theory

Illocutionary acts

Speech act theory was proposed by J. L. Austin and has been developed by J. R. Searle. Basically, they believe that language is not only used to inform or to describe things, it often used to “do things”, to perform acts. For example, if you work in a company where the boss has the overwhelming power, then the boss’s utterance (16) is more than just a statement.

You’re fired.

This utterance can be used to perform the act of ending your employment. Some other utterances like “I hereby name this ship Red Flag”, “I bet you five

It is argued that even non-performative sentences are used to perform acts. On some occasions, for instance, in saying “It’s such a fine day today” someone may be performing the act of suggesting an outing. So it is claimed that all sentences, in addition to whatever they mean, perform specific actions or “do things” through having specific forces. Austin suggests three basic senses in which in saying something one is doing something and three kinds of acts are performed simultaneously:

Locutionary act: the act of saying, the literal meaning of the utterance;

Illocutionary act: the extra meaning of the utterance produced on the basis of its literal meaning;

Perlocutionary act: the effect of the utterance on the hearer, depending on specific circumstances. Suppose the speaker says:

It’s stuffy in here.

The locutionary act is the saying of it with its literal meaning “There isn’t enough fresh air in here”. The illocutionary act can be a request of the hearer to open the window. The perlocutionary act can be the hearer’s opening the window or his refusal to do so. In fact, we might utter (17) to make a statement, a request, an explanation, or for some other communicative purposes. This is also generally known as the illocutionary force of the utterance. But how do people know which speech act is intended? A possible answer is to specify felicity conditions—circumstances under which it would be appropriate to interpret something as a particular type of speech act. For example, if a genuine order has been issued, the hearer must be physically capable of carrying it out (“Get me a star” is not), and must be able to identify the object involved.

The literal meaning is taken care of by semantics and the effect of an utterance is subject to many factors, including social psychology, more than linguistics can cope with. So, what speech act theory is most concerned with is illocutionary acts. It attempts to account for the ways by which speakers can mean more than what they say. It is also designed to show coherence in seemingly incoherent

conversations. Consider:

a. Husband: That’s the phone.

b. Wife: I’m in the bathroom.

c. Husband: Okay.

This is an exchange between husband and wife when the telephone rings. In (18a) the husband is not describing something—it is a thing that needs no description to his wife. In saying (18a), he is making a request of his wife to go and answer the phone. In (18b), the wife is not describing her action either— people do not usually need to assert that they are in the bathroom. Its illocutionary acts are (i) a refusal to comply with the request and (ii) issuing a request to her husband to answer the phone instead. In (18c) the man accepts his wife’s refusal and accepts here request, meaning “All right, I’ll answer it.” This analysis shows that this seemingly unconnected conversation is very coherent on a speech-act level (in b and c, each performs two speech acts), and that in saying things people are in fact “doing” things.

Classification of illocutionary acts

We might be very curious as to how many illocutionary acts can be performed using language. Obviously, we cannot just list all the performative verbs as all the possible types of illocutionary acts. For one thing, that would be too long a list to be useful as a linguistic generalization. Secondly, there are verbs which can describe illocutionary acts but cannot be used as performative verbs. We can describe an act as an “insult”, for example, but it would be very unusual to say “I hereby insult you”. Thirdly, many sentences have an illocutionary force without using performative verbs as example (17). Searle suggests five basic categories of illocutionary acts:

Representatives

a. The earth is flat.

b. It was a warm sunny day.

c. Chomsky didn’t write about music.

In using a representative, the speaker makes words fit the world (of belief). Of course, the degree of commitment varies from statement to statement. The commitment is small in “I guess John has stolen the book” but very strong in “I solemnly swear that John has stolen the book”.

Directives

a. Gimme a cup of coffee. Make it black.

b. Could you lend me a pen, please?

c. Don’t touch that.

In using a directive, the speaker attempts to make the world fit the words (via) the hearer.

Commissives

a. I’ll be back.

b. I’m going to get it right next time.

c. We will not do that.

In using a commissive, the speaker undertakes to make the world fit the words (via the speaker).

Expressives

illustrated in (22), they can be caused by something the speaker does or the hearer does, but they are about the speaker’s experience.

a. I’m really sorry!

b. Congratulations!

c. Oh, yes, great, mmm. ssahh!

In using an expressive, the speaker makes words fit the world (of feeling).

Declarations

a. Priest: I now pronounce you husband and wife.

b. Referee: You’re out!

c. Jury Foreman: We find the defendant guilty.

In using a declaration, the speaker changes the world via words.

Indirect speech acts

A different approach to distinguishing types of speech acts can be made on the basis of structure. A simple structural distinction between three general types of speech acts is provided, in English, by the three basic sentences types. As shown in (24), there is an easily recognized relationship between the three structural forms (declarative, interrogative, imperative) and the three general communicative functions (statement, question, command/request).

a. declarative: You wear a seat belt. (statement)

b. interrogative: Do you wear a seat belt? (question)

c. imperative: Wear a seat belt! (command/request)

whenever there is a direct relationship between a structure and a function, we have a direct speech act. However, this is not always the case. In fact, very often people seem to prefer not to be direct and explicit in the performance of speech acts. For example, a declarative used to make a statement is a direct speech act, but a declarative used to make a request is an indirect speech act. As illustrated in (25), the utterance in (25a) is a declarative. When it is used to make a statement, as paraphrased in (25b), it is functioning as a direct speech act. When it is used to make a command/request, as paraphrased in (25c), it is functioning as an indirect speech act.

a. It’s cold outside.

b. I hereby tell you about the weather.

c. I hereby request of you that you close the door.

One of the most common types of indirect speech act in English, as shown in (26), has the form of an interrogative, but is not typically used to aske questions, that is, we do not expect an answer, but we expect action. The examples in (26) are normally understood as requests:

a. Could you pass me the salt, please?

b. Would you open this for me?

Indeed, there is typical pattern in English whereby asking a question about the hearer’s assumed ability (“Can/Could you?”) or future likelihood with regard to doing something (“Will/Would you?”) normally counts as a request to actually do something.

Requests are often performed indirectly. Their indirectness has certain characteristics that tend to group requests into the following types:

Group 1: Sentences concerning the hearer’s ability to do something (some examples below are quoted from Searle):

a. Can you pass the book over?

b. Could you type the paper for me?

Group 2: Sentences concerning the speaker’s wish or want that the hearer will do something:

a. I would like you to write this down.

I would appreciate it if you could do it for me.

I’d rather you didn’t do that any more.

I’d be very much obliged if you would take me there. Group 3: Sentences concerning the hearer’s doing something:

a. Would you kindly pick that up for me?

b. Wouldn’t you turn the TV down a little?

Group 4: Sentences concerning the hearer’s desire or willingness to do something:

a. Do you want to return these books for me now?

b. Would it be convenient for you to come over on Friday afternoon?

c. Would it be too much trouble for you to type the paper for me? Group 5: Sentences concerning reasons for doing something:

a. You should write to them every now and then.

b. Must you make that noise when you are reading?

c. You’d better book the tickets two weeks in advance.

Sometimes sentences are used that have more than one of these elements, with one inside another:

Would it be too much trouble if I suggested that you could possibly return these books for me?

Principle of conversation

As the objective of pragmatic study is to explain how language is used to effect successful communication, conversation, as the most common and natural form of communication, has drawn the attention of many scholars. It has been noted that in the course of conversation people do not always express themselves literally; instead sometimes they use implications. Compare the two examples below:

a: What the time? b: It’s ten o’clock.

a: What the time?

b: The bell has just rung.

In both examples, the first speaker asks the same question, wanting the hearer to tell him the time. In (33), the hearer tells the time in an explicit and specific manner, satisfying the speaker’s communication need. But in (34), instead of giving an explicit answer to the question, the second speaker chooses to send an implied message. In this case the first speaker’s communication need is also satisfied, but he has to work out the time by making some inference based on their common knowledge that, say, the bell normally rings at ten o’clock.

A philosopher and logician, H. P. Grice took great interest in the way conversations are carried out, especially how implied meanings are generated and understood. Grice specified two kinds of implied meaning or implicature: Conventional implicature and non-conventional implicature.

Conventional implicature is based on the conventional meaning of certain words in the language.

For example:

He is rich but he is not greedy.

According to Grice, (35) has the implication that rich people are usually greedy, and this implicature is derived from the conventional meaning of the word

Of the types of non-conventional implicature, Grice singled out as his focus of study particularized

conversational implicature, which, according to Grice, is inferred by the hearer with reference to the context of communication. For example:

a: Where is the steak?

b: The dog looks very happy.

The implicature of the second utterance is that the dog has eaten the steak. The first speaker can only manage to recognize this implicature by making inferences based on the context of conversation.

The Cooperative Principle and its maxims

In Grice’s view, to converse with each other, the participants must first of all be willing to cooperate; otherwise, it would not be possible for them carry on the talk. This general principle is called the Cooperative Principle (CP). It is, so to speak, the prerequisite for any conversation to take place. In Grice’s wording, it goes as follows:

Make your conversational contribution such as is required at the stage at which it occurs by the accepted purpose or direction of the exchange in which you are engaged.

To be more specific, there are four maxims under this general principle:

The maxim of quantity

Make your contribution as informative as is required (for the current purpose of the exchange).

Do not make your contribution more informative than is required.

The maxim of quality

Do not say what you believe to be false.

Do not say that for which you lack adequate evidence. The maxim of relation

Be relevant.

The maxim of manner

Avoid obscurity of expression.

Avoid ambiguity.

Be brief (avoid unnecessary prolixity).

Be orderly.

To put it very simply, the CP means that we should say what is true in a clear and relevant manner. It is important to take these maxims as unstated assumptions we have in conversations. We assume that people are normally going to provide an appropriate amount of information, and that they are telling the truth, being relevant, and trying to be as clear as they can. Speakers rarely mention these principles simply because they are assumed tacitly in verbal interactions.

Conversational implicature

Grice’s basic idea is that in communication, speakers aim to follow the CP and its maxims, and that hearers interpret utterances with these maxims in mind. According to Grice, utterance interpretation is not a matter of decoding messages, but rather involves (i) taking the meaning of the sentences together with contextual information, (ii) using inference rules, and (iii) working out what the speaker means on the basis of the assumption that the utterance conforms to the maxims. The main advantage of this approach form Grice’s point of view is that it provides a pragmatic explanation for a wide range of phenomena, especially for conversational implicatures—a kind of extra meaning that is not literally contained in the utterance.

According to Grice, conversational implicatures can arise from either strictly and directly observing or deliberately and openly flouting the maxims, that is, speakers can produce implicatures in two ways: observance and non-observance of the maxims.

The least interesting case is when speakers directly observe the maxims so as to generate

conversational implicatures.

Husband: Where are the car keys? Wife: They’re on the table in the hall.

The wife has answered clearly (Manner) and truthfully (Quality), has given just the right amount of information (Quantity) and has directly addressed her husband’s goal in asking the question (Relation). She has said precisely what she meant. In this case, there is, in essence, no distinction to be made between what is said and what is implicated.

However, in actual speech communication, it is often the case that speakers cannot or do not observe the CP and its maxims. For example:

His is a tiger.

Tom has wooden ears.

Example (38) is literally false, openly against the maxim of quality, for no human is a tiger. But the hearer still assumes that the speaker is being cooperative and then infers that he is trying to say something distinct from the literal meaning. He can then work out that probably the speaker meant to say that “he has some characteristics of a tiger”. Sentence (39) is obviously false (in most natural contexts) and the speaker in uttering it flouts the first maxim of quality: do not say what you believe to be false. Hence, the hearer infers that the speaker meant something informative instead, for example, (40). Metaphors and irony are standard examples of the flouting of the maxim of quality.

Tom does not appreciate classical music so we should not invite him to the concert.

In (41), the second speaker violates the maxim of quantity by providing less information than is required:

a: Where does C live?

b: Somewhere in the South of France.

This violation can be explained by the adherence to the maxim of quality: the second speaker cannot truthfully provide more detailed information. Alternatively, in some contexts, it can be explained as carrying an implicature that the speaker does not, for some reason or other, want to reveal C’s precise location. If the maxims are breached, the hearer infers that the speaker must have meant something else, that is, the speaker must have had some special reason for not observing the maxims. In example (42), flouting the maxim also leads to implicatures.

If he comes, he comes.

Sentence (42) is a tautology. It is uninformative by virtue of its semantic content. In uttering it the speaker flouts the first maxim of quantity: the contribution to conversation is not sufficiently informative. Assuming that the maxim of quantity is preserved after all, the hearer infers that the speaker meant something more informative, for example:

You never know if he is going to turn up so there is no point worrying about it.

The utterance like “Girls are girls” and “War is war” are typically “informationless” but are in fact rich in meaning. To such things, the hearer would not say “Nonsense! I know girls are girls, not boys!” He would infer from the specific context that the speaker probably means that girls are careful, thoughtful, and considerate or like to talk about shopping and fashion.

In addition, giving more information than required may also be taken as have other motives than the utterance suggests. For a man to introduce himself to a girl at a party by saying

I‘m Alex from Leeds, 26, unmarried.

would make the girl suspicious of his motive.

The maxims of relation and manner can also not be observed. For example:

a: I’m out of petrol.

b: There is a garage round the corner.

a: Shall we get something for the kids? b: Yes. But I veto I-C-E-C-R-E-A-M.

in (45), the second speaker would be infringing the maxim “Be relevant” unless he thinks, or thinks it possible, that the garage is open and has petrol for sale; so he implicates that the garage is, or at least may be open, etc. and (46) can only be said when it is known to both speakers that the second speaker has no difficulty in pronouncing the word

From the examples above, we can see clearly that this pattern of conversational inferences can work only on the assumption that he interlocutors share some background knowledge that allows the speaker to produce adequate utterances and the hearer to infer what was assumed by the speaker. In other words, the speaker has to tailor his/her utterances so as to ensure that the implied meaning can in fact be recovered.

The Politeness Principle

The Cooperative Principle alone cannot fully explain how people talk. It explains how conversational implicature is given rise to but it does not tell us why people do not say directly what they mean. Why, for instance, do people say “Could you give me a lift?” instead of “Give me a lift”? The reason has to do with another principle which applies to conversation in addition to the Cooperative Principle—the Politeness Principle (PP).

In most cases, the indirectness is motivated by considerations of politeness. Politeness is usually regarded by most pragmatists as a means or strategy which is used by a speaker to achieve various purposes, such as saving face, establishing and maintaining harmonious social relations in conversation. Leech looks on politeness as crucial in accounting for “why people are often so indirect in conveying what they mean”. He thus puts forward the Politeness Principle so as to “rescue the Cooperative Principle” in the sense that politeness can satisfactorily explain exceptions to and apparent deviations from the CP. Therefore, his Politeness Principle is not just an addition to Grice’s CP, but a necessary complement needed for cases where the CP fails to offer a reasonable explanation.

Following Grice’s presentation of the CP, Leech puts forward six maxims of the Politeness Principle which runs as follows:

Minimize (other things being equal) the expression of impolite beliefs and maximize (other things being equal) the expression of polite beliefs.

The six maxims of the PP:

Maxim of Tact (in directives and commissives)

Minimize cost to other

Maximize benefit to other

Maxim of Generosity (in directives and commissives)

Minimize benefit to self

Maximize cost to self

Maxim of Approbation (in expressives and assertives)

Minimize dispraise of other

Maximize praise of other

Maxim of Modesty (in expressive and assertives)

Minimize praise of self

Maximize dispraise of self

Maxim of Agreement (in assertives)

Minimize disagreement between self and other

Maximize agreement between self and other Maxim of Sympathy

Minimize antipathy between self and other

Maximize sympathy between self and other

Briefly, this principle requires speakers to “minimize the expression of impolite beliefs”. These maxims can help to explain, among other things, why certain forms are more acceptable than others. In British culture, for example, the Politeness Principle probably accounts for the use of “white lies” in conversation. For instance, if someone invites another person to a party and that person wants to decline the invitation, rather than saying “No, I don’t want to come” the person might pretend to have another engagement and say “Thank you, but I’m going out that evening”. Of course, after repeated invitations which are repeatedly declined with statements like “I’m afraid I’m busy” or “I have another engagement”, the inviter will probably “get the message” and stop inviting. White lies must of course be properly deceptive. Imagine someone who declined an invitation for dinner the following weekend by saying “I think I’m going to have a headache”. In its transparency this “white lie” is a failure—it breaks the Politeness Principle—and is perhaps even more impolite than a simple direct refusal.

Very often a superficial view is taken of politeness in spoken language—it is associate with being superficially “nice”, and with formal, mechanical exptras such as the word

The Maxim of Approbation will explain why a compliment like “What a marvelous meal you cooked!” is highly valued while “What an awful meal you cooked!” is not socially accepted. Thus when criticism is inevitable, understatement is preferred as a show of reluctance to dispraise (Cf. “Her composition was not so good as it might have been”). The maxim of modesty accounts for the benign nature of utterances like “How stupid of me!” and the offensive nature of “How clever of me!” Regulated by the maxim of agreement, people tend to exaggerate their common ground first, even when much difference is to follow:

a: The book is very well written.

b: Yes, well written as a whole, but there are some rather boring patches, don’t you think?

In the following example, notice how much effort the second speaker puts into trying to hide the fact that the first speaker thinks one thing (the female being discussed is “small”) and he thinks t he opposite.

a: She’s small, isn’t she?

b: Well, she’s sort of small…certainly not very large…but actually…I would have to say that she is large rather than small.

This conversation is very different indeed from the following simple expression of disagreement:

a: She’s small, isn’t she? b: No, she’s large.

If expressing disagreement is inevitable, then speakers attempt to soften it in various ways, by expressing regret at the disagreement (“I’m sorry, but I can’t agree with you”). Notice in this example, the use of the word

The Maxim of Sympathy has such a regulative force that we invariably interpret (50) as a

congratulation and (51) as a condolence:

I’m delighted to hear about your cat.

(Most likely the cat has just won a prize in the cat-show.)

I’m terribly sorry to hear about your cat. (Probably the cat has just died.)

It is argued that when the CP and PP are in contradiction, it is generally the CP maxims that get sacrificed. When the truth cannot be told for politeness sake, a white lie may be offered. In fact the PP is so powerful that people are often encouraged to violate its maxims in order to ensure a cooperative discourse (Don’t be too modest. Tell us everything you’ve achieved.” “If you find anything inadequate in the pater, don’t hesitate to point it out.”) Irony is a means to solve the conflict between the CP an PP— when the truth is too offensive to be told, an ironic utterance assumes a polite surface while delivering an unpleasant true message underneath.

An interesting area of investigation is the study of different cultures and languages in relation to the social principles of conversation. For example, some cultures may place a very high value on the Maxim of Agreement and speakers may show this by repeating every word the other speaker has just said—as if they agree totally—and then giving their own opinion. The British, for example, are supposedly well- known for the use of “Yes, but…” replies. There is much interesting and important research to be done in this area.

Cross-cultural pragmatics failure

As we know, in the course of communication breakdowns sometimes occur. There are a number of possible causes. Sometimes it is the structure the language itself that is causing the trouble; sometimes it is because the speaker fails to communicate effectively to the hearer; and sometimes it is because the hearer fails to see the speaker’s intention of speaking. Here are some examples:

(Between a passenger and the bus driver)

Passenger: Can you tell me when we get to Birmingham, please? Driver: It’s a big place. You won’t miss it.

(Between the hostess and a party guest when it is nearly midnight and most of the guest have left)

Hostess: It’s really been a long day, Leo. I think Steve can give you a lift back home. Guest: Oh, I’m fine. Can I have another cup of coffee, please?

(Between a Chinese learner of English and Professor Higgins, a native speaker of English, at about lunch time)

Chinese learner: Have you had your lunch, Professor Higgins? Professor Higgins: … (Surprised, not knowing what to say)

In (52), the trouble is caused by the different interpretations of the when-clause. The passenger intends it to be an object-clause, asking the time when the bus will reach Birmingham, yet the driver takes it to be an adverbial clause of time. In (53) the real intention of the hostess is to tell the guest Leo that it is time for him to leave, but Leo obviously fails to see her intention. The error committed by the Chinese learner of English in (54) is quite common among Chinese learners of English at the elementary level. They think they are greeting the foreign professor, but asking whether someone has eaten around meal time is not a proper way to greet others in English.

Of the three causes of communication breakdowns illustrated in the examples above, the latter two have to do with pragmatic studies and thus are our concern. The technical term for such breakdowns is

pragmatic failure. Pragmatic failure occurs when the speaker fails to use language effectively to achieve a specific communicative purpose, or when the hearer fails to recognize the intention or the illocutionary force of the speaker’s utterance in the context of communication. Pragmatic failure may occur in intra- cultural communication, i.e. between speakers of different cultural backgrounds. The reason is obvious: different languages differ not just in form, but also in use. In our discussion of pragmatic failure, we will confine ourselves to the latter case.

Pragmatics is assumed to have two dimensions: pragmalinguistics and sociopragmatics. Pragmalinguistics is applied to the more linguistic end of pragmatics, i.e. how the linguistic forms of a language are used to serve specific pragmatic purposes. Sociopragmatics is the sociological interface of pragmatics; it is concerned with the customary ways in which people of a particular culture behave to achieve a particular purpose. Correspondingly, there are two kinds of pragmatic failure: pragmalinguistic failure and sociopragmatic failure, although the two are related and cannot always be distinguished.

Instances of pragmatic failure are often found in the English used by foreign learners of it. For example, as we Chinese can use “没关系” as a response to an expression of thanks, some learners of English tend to use its literal English translation “It doesn’t matter” as a response to an expression of thanks in English. This is a case of pragmalinguistic failure. The speaker is transferring a form in his own language to a foreign language, wrongly assuming that it performs the same communicative function. In fact, the same linguistic form is not always associated with the same illocutionary force in different languages. This also explains why “Have you had your lunch?” is not an appropriate way to greet a speaker of English around lunch time.

Another example of pragmatic failure is the way in which speakers of Chinese respond to compliments. When complimented, a speaker of Chinese tends to deny the truth of the compliment as a way of showing modesty, which is a much-valued virtue in the Chinese culture, as in

a: You speak beautiful English.

b: No, no, no. My English is still very poor.

This is very different form the way speakers of English react to a compliment. They will accept it with good grace.

Also, speakers of Chinese and English differ in the way they start a conversation, especially with someone they are not yet very familiar with. As we all know, the Chinese like to ask personal questions in order to shorten the distance while the English speakers, trying to avoid intrusion into others’ privacy, would normally begin by talking about the weather or other non-personal topics. Keeping asking an English speaker question about his age, his income, his marital status, etc. with the good intention to make friends with him would be a typical case of sociopragmatic failure.

To familiarize ourselves with the pragmatics of the foreign language we are learning is of essential importance. When we learn a language, we do not just learn its vocabulary and rules of grammar, we should also learn its rules of use so as to avoid pragmatic failure.

查看更多

视觉传达设计就业方向思维导图

U261165379

U261165379树图思维导图提供《视觉传达设计就业方向思维导图》在线思维导图免费制作,点击“编辑”按钮,可对《视觉传达设计就业方向思维导图》进行在线思维导图编辑,本思维导图属于思维导图模板主题,文件编号是:d627dbed2cd6c34d195cf60767d8853f

大学生职业生涯规划思维导图

U547267440

U547267440树图思维导图提供《大学生职业生涯规划思维导图》在线思维导图免费制作,点击“编辑”按钮,可对《大学生职业生涯规划思维导图》进行在线思维导图编辑,本思维导图属于思维导图模板主题,文件编号是:c12f9c3431ab72674f6ac3c30e79a571

相似思维导图模版

首页

我的文件

我的团队

个人中心